Beshalach: The Beginning of the Road to Freedom

Transcript

This week, I’m only doing four faces of Torah: inspirational, political, trivial and structural. I do go into a fair amount of detail, so bear with me and let me know if it is too much.

As with last week, these divrai Torah are also dedicated to the memory of someone who passed away recently. Her name was Sheila Rubenstein. I’ll tell you more about her and her connection to this reading/parsha at the end of the podcast.

These are difficult days, many people are passing away, we should all do what we can to spread the positive impacts of those who have left us.

I’m doing these podcast in memory of these people, in part, because it is one way in which I can help.

Inspirational

When I read this parsha, I am struck by the attitudes of the people involved. On the one hand, there are two million Jews and they are afraid of 600 Egyptian chariots. There are literally 3,000 people per chariot and they are frozen in fear. This speaks to the slave mentality, which we’ll get to in a bit.

But what I want to focus on first, in this section, is the mentality of the Egyptians themselves. Yes, Hashem hardens the heart of Pharaoh and his servants. But the Egyptian people are excluded from this group. They join Pharaoh in his pursuit. Despite everything, they join Pharaoh in his chase of the Jewish people. Later, Hashem says he will harden the heart of the Egyptians. But He never actually does so.

He doesn’t need to.

On the other hand, even after all the plagues, the Egyptian army is ready to plunge into the midst of a split sea in pursuit of their prey. Only when the wheels of their chariots begin to fall off do they recognize their position and flee. They cry out:

Let us flee from the face of Israel, because Hashem fights for them in Egypt.

What took them so long?

Let’s take an Egyptian perspective. Yes, there were 10 terrible plagues. Yes, they had pushed the Bnei Israel out. But that wasn’t the end of the story. The Bnei Yisrael had claimed they would be gone for three days, but they had already violated that claim. They weren’t trustworthy. The Bnei Yisrael had said they were going to the wilderness to serve Hashem, but they had offered no sacrifices. And then the pillar of fire and the pillar of cloud had led the Jewish people into a trap. As if that was what G-d intended.

The Egyptians themselves had been freed through the plagues. Remember, they had been enslaved by Yosef. Perhaps they believed they were blessed and the Jewish people were the vehicle of their redemption.

It all seems like a stretch, but it is surprisingly easy to recast reality to tell whatever story you already happen to believe. We do it all the time. Just look at the economic analysis Republicans and Democrats engage in every day. No matter the facts are, each side will find a way to have them tell their story.

Hashem leaves the Egyptians able to think this way. The pillar hides what is happening in front of them. It could be a buffer between the peoples, but it could also be a guidepost, telling the Egyptians where to go.

But once the waters split? How could the Egyptians still believe then? How could they not understand something else was going on? How could they not actually need their hearts hardened before they chase the Bnei Yisrael into the sea?

The answer comes right before their moment of realization.

And He took off their chariot wheels, and made them to drive heavily; so that the Egyptians said: ‘ Let us flee from the face of Israel, because Hashem fights for them in Egypt.’

They realize what is happening when the wheels of their chariots literally fall off.

If we look back over the plagues, we see nature from the waters below to the waters above conspiring against Egypt. We see nature from the past to the future conspiring against Egypt.

But technology – the creations of man? It had never turned against Egypt. Egypt’s civilization was a story of humankind controlling and harnessing nature. They turned wheat and bacteria into bread. They made paper, they constructed massive pyramids and public works. By this time, in their story, they had learned to sale against the wind and built ships as large as 360 tons – bigger than all three of Columbus’ ships combined. They appeared to have mastered the use of concrete with some arguing the pyramids were actually poured concrete, not stone.

The Egyptians were technological masters of their world.

And that is why the Torah tells us only about their chariots. The number of men they mustered. That wasn’t important. What was important was the number of ancient main battle tanks.

This was the might of Egypt.

And G-d had not touched it.

The Egyptians were masters of their world. They were gods.

Because of their technology.

They were willing to chase the people into the waters because of their technology.

And they fled, finally recognizing the totality of Hashem’s power, when that technology failed them. When the wheels came off and the chariots began to drive heavily.

Interestingly they don’t say Hashem is fighting kneged Egypt – ‘against’ Egypt. Instead, He is fighting within Egypt. In this context, Egypt isn’t a place – they are in the middle of the sea.

Egypt is her technical might.

With this plague, Hashem undermines the last frontier of Egyptian strength. He has not only shown His mastery of nature, he has shown His mastery over their own handiwork.

Only with this plague is the lesson complete.

The lesson for us is straight-forward. We should not imagine that we are gods simply because of our mastery over our own world. And we should not imagine that we have a right to enslave others because of our technological development.

If we do this, we may be greatly surprised when the wheels come off.

In recent years, our mastery of our own world has entered an entirely new phase. We are on the cusp of being able to read, and effectively and efficiently edit, every aspect of our own genetic code. We can redefine ourselves on a most fundamental physical level. Our power seems unlimited.

Our technology has moved beyond the physical and mechanical and electronic and into life itself.

We are like gods.

Or at least, we could see ourselves as being like gods until the year 2020. Yes, our technology might rescue us.

But there is a significant chance that our technology created the monster in the first place.

New York Magazine, hardly a bastion of conspiracies, did a piece that included discussion of some of the close calls of the past.

In 1977, a worldwide epidemic of influenza A began in Russia and China; it was eventually traced to a sample of an American strain of flu preserved in a laboratory freezer since 1950.

In 1978, a hybrid strain of smallpox killed a medical photographer at a lab in Birmingham, England; in 2007, live foot-and-mouth disease leaked from a faulty drainpipe at the Institute for Animal Health in Surrey. In the U.S., “more than 1,100 laboratory incidents involving bacteria, viruses and toxins that pose significant or bioterror risks to people and agriculture were reported to federal regulators during 2008 through 2012,” reported USA Today in an exposé published in 2014.

In 2015, the Department of Defense discovered that workers at a germ-warfare testing center in Utah had mistakenly sent close to 200 shipments of live anthrax to laboratories throughout the United States and also to Australia, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and several other countries over the past 12 years. In 2019, laboratories at Fort Detrick — where “defensive” research involves the creation of potential pathogens to defend against — were shut down for several months by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for “breaches of containment.”

We imagine we’re gods. Whether or not this virus is ‘natural’, this experience should remind us that we are not.

The wheels can easily come off our chariots as well.

It would behoove us to remember our limits before we run headlong into the midst of the waters.

Political

Now, I want to discuss the perspective of the bnei Yisrael. They, of course, do not imagine themselves as gods. Their perspective is very very different. The Torah calls them Chamushim – or ‘Fivers’. There are various attempts to understand this. I tend to look for earlier instances of words or concepts to understand their later symbolic meaning.

Five doesn’t come up much. But it does come up in the story of creation. On the fifth day, Hashem created every living creature that creeps. He created insects. They are calls Sheretz Nefesh Chaya animated life that sheretz – that creeps.

At the beginning of the book of Shemot, the people not only The Jewish people are indirectly compared to insects at the beginning of the book of Exodus. When man is created, we are to peru urvu – “be fruitful and multiply”. But the Jewish people in Egypt peru v’shirtzu urvu – “they are fruitful, they swarm and they multiply.”

They are Chamushim. They are Fifth Dayers. They are like insects.

This is why they are so frightened of Pharaoh’s army. Even with the giving of the Pesach offering, they are far from free actors. In the face of the Egyptians, they are like bugs. They can be crushed.

In fact, later on, they see themselves as like bugs in the face of the Canaanites. They call themselves grasshoppers in the eyes of the Canaanite giants. This image sticks with them.

As I read it, the rest of the Chumash is about taking a people out of slavery. It is about making free people, dedicated to the timeless, out of slaves who can not plan past the present.

And it all starts here.

After the Egyptians are cast into the sea, after the Jewish people see their bodies on the shore, they sing a song. They sing the famous Az Yashir Moshe. And after that, Miriam the prophetess sings the central verse of that song: “Sing to G-d because he is pride of prides. The horse and rider he throws into the sea.”

Hashem has shown his pride, yes. He has shown that even the greatest of the sons of the powerful are still but men. But the second part of the verse lays out what is yet to come.

On one level, the horse and rider have been cast into the sea. But why would that be a critical part of the story? There are 600 chariots that had our attention not long before. Why not use one of those verses as a highlight: “Pharaoh’s chariots and his host hath He cast into the sea, and his chosen captains are sunk in the Yam Suf.”

Why the horse and rider?

Satre wrote a famous line about the Algerian-French conflict. He wrote: “To shoot down a European is to kill two birds with one stone, to destroy an oppressor and the man he oppresses at the same time: there remains a dead man and a free man.”

I think the verse about the horse and the rider isn’t about the Egyptians, it is about the Jewish people. The Jewish people were the slaves of Egypt. They were the pack animals. The Torah seems to compare them to insects, but perhaps they compared themselves to horses. They were tamed, domesticated, controlled. They were broken.

But with the drowning of the Egyptian army, suddenly, those horses are gone. To paraphrase Sartre, “To drown an Egyptian is to kill two birds with one stone, to destroy an oppressor and the man he oppresses at the same time: there remains a dead man and a free man.” You destroy the horse and rider and there remains a free people.

This process, the process of truly realizing one’s freedom, is out of reach for most slaves. Slavery haunts the enslaved for generations, or even centuries. Like victims of a rape seeing their rapists before them, slaves have a truly difficult escaping the past.

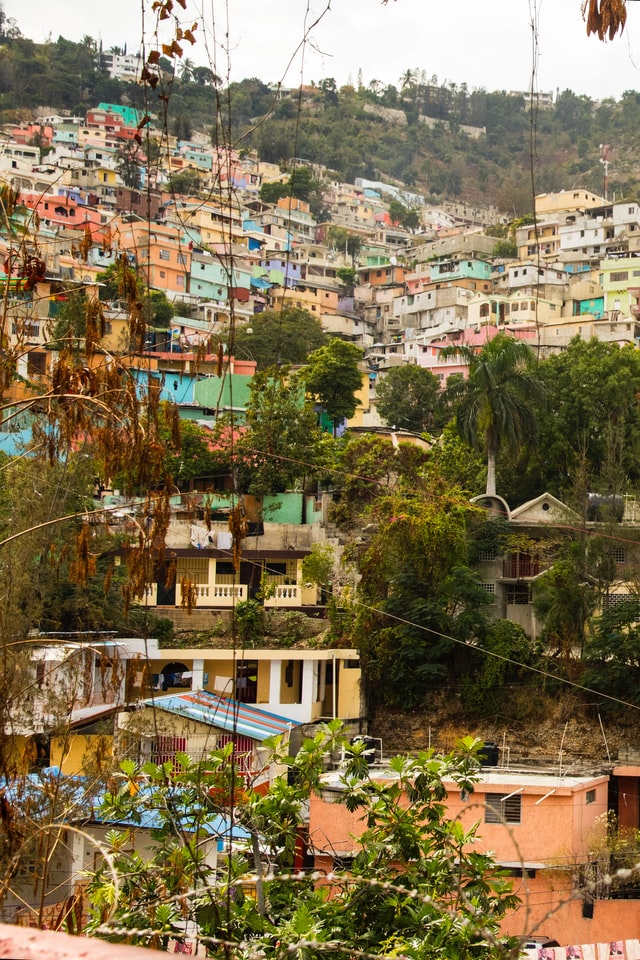

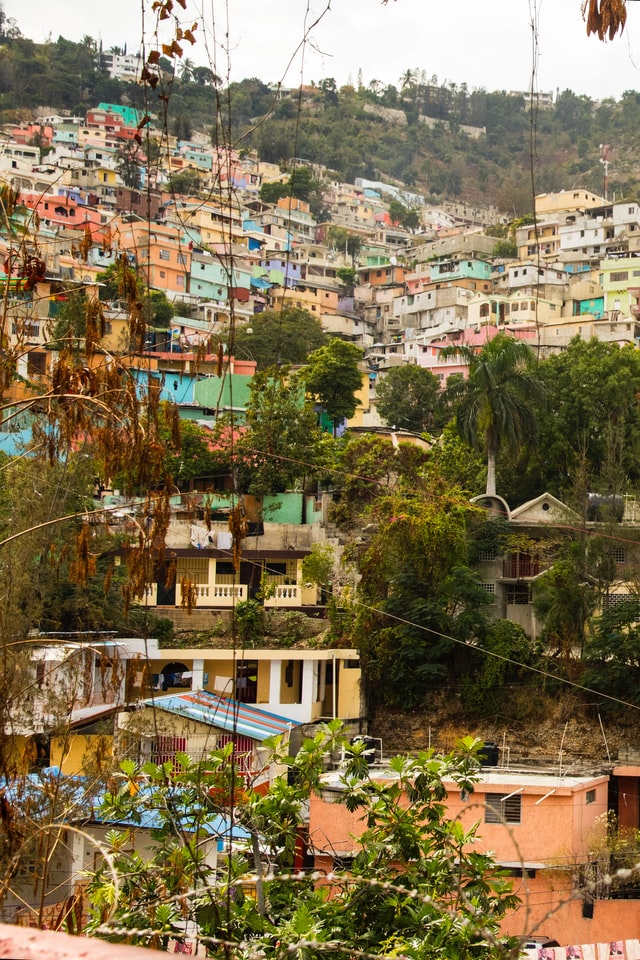

The Haitians are a classic example. They are the only people, ever, to successfully mount a successful slave revolt. They tried to replicate the crossing of the sea. They killed every white person on the islands in a fit of slaughter. But it did not grant them freedom. They remained barricaded and broken and ruled by a dictator until he died. They remain broken even today.

What is important is not to kill your oppressor. What is important here is a change of mindset.

What the Jewish people see is not just the bodies on the shore. The Jewish people recognize that the people who once occupied those bodies – the nation behind them – has no real power over them.

Natan Sharansky once said about his time in prison: “I liked very much during interrogations, to tell [the team of interrogators] anti-Soviet jokes… they were almost bursting with laughter and they could not [laugh]. And I said to them, ‘You cannot even laugh when you want to laugh, and you want to tell me that I’m in prison and you’re free?’”

The lesson is clear: freedom is a mindset. The destruction of Pharaoh’s army wasn’t about killing the Egyptians. They could always raise another army. It was about the Jewish people learning that they were protected. It was about realizing that a greater power was protecting them.

This realization, more than any physical reality, is the first step on the road to freedom.

Trivial

#1) I missed this in the prior episode. But we have the commandment to axe the neck of donkey if we don’t redeem it. Why? If the Jewish people don’t dedicate their future to Hashem, as we see with the pesach offering and dedication of the first born, then they are being stubborn like the donkey. They are being stiffnecked. In this case, there is no reason for their survival. The axing of the donkey’s neck – which you’d never actually do because a lamb is worth less and can be eaten – is a reminder that we don’t actually have to sacrifice ourselves to dedicate our future to G-d.

#2) Moshe continues the tradition of the unvoiced prayer in this reading. Even though no words are recorded, we know Moshe prays to Hashem because G-d says to him: “Why do you cry out to me?” The Torah never says Moshe cried out. He was telling the people to trust. Instead, it is his soul calling to Hashem. Calling for protection. Hagar, Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaacov all have similar unvoiced prayers. The prayers they utter when they cannot go on without divine intervention.

#3) In the Pesach Seder we compare the number of plagues in Egypt to those at the Sea. The discussion seems farcical. Why would we think the splitting of the sea is somehow the equivalent of 50 or 250 plagues in Egypt? It is like a child asking which is better: a monkey or a car. It is a nonsensical comparison. But perhaps this numerical analysis is actually a struggle to grasp something far more fundamental.It took 10 plagues to convince the Egyptians to act freely and chase out the Jewish people. Remember that the Egyptians had been enslaved Yosef. Of course, the Egyptians had imagined themselves as masters – freedom was not so hard to grasp. They went into the sea, after all, as free people.

The Jewish people were different. They saw themselves as slaves. And so it took 250 plagues to convince the Jewish people of their own freedom.

#4) My brother points out that the miracle occurred before the gods of Egypt and Canaan. It happens before the mouth of Chirot and in front of Ba’al Tzephon. Ba’al Tzefon literally means the master of the North. This would seem to be a divine boundary between the edge of Egypt and Canaan – between the gods of Egypt and the gods of Canaan.

But the Egyptian god seems to foreshadow for what is about to occur to the Egyptians. To quote the Ancient History Encyclopedia: “Cherti was a ram-headed god of the underworld who ferried the dead on their last journey into the afterlife.The dead were greeted by other deities when they arrived in the afterlife and were then brought to the Hall of Truth for judgment by Cherti.”

#5) In Az Yashir, the Jewish people plant the seeds of future troubles. The first is that they see themselves as having been horses, when the Torah seems to put them a little lower on the food chain. The second is how they see the source of their redemption. “Azi v’Zimrat Ya v’yehi li lishua” if literally translated means “my strength and the tune of G-d has become my salvation”. There are other ways people translate this. Rashi, for example, goes to great pains to argue the yud at the end, which normally implies “my” is actually just part of the noun for strength. He translates it as “The strength and vengeance of our G-d has become to us a help.” But if we read it in the simplest sense, we can see the first seed of a growing self-worship we’ll see flowering later.

The Jewish people ascribe some aspect of their redemption to their own strength. There’s a reason Hashem has to keep reminding the people that He brought us out of Egypt – we seem to have particularly hard time remembering that.

#6) Here’s a fun one. Why is Az Yashir laid out like it is? The answer is actually pretty simple. The two sides that wave in and out are the waters, you can see them waving. The middle is the column of the people marching through the waters. Don’t believe me? In many printings you can find proof in the last line of the song. On the left is the word “Yam” for sea. On the right is the word “Yam” and in the middle is the phrase “וּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל הָלְכוּ בַיַּבָּשָׁה, בְּתוֹךְ” “And the Jewish people walked on firm land in the middle.”

This is arguably the only picture in Chumash – ASCII art. I think it speaks to the childlike nature of the people at this time. They learn with food – like Matzah and bitter herbs – and they learn with pictures.

Structural

For the structural part I’m going to dip back into the process of freedom. This process is critical to human fulfillment and we’ve seen it falter so often. Some revolutions succeed, as in the Czech Republic or Poland. But many many revolutions fail. The Arab Spring was largely a series of failures. Putin’s current power in Russia suggests the Russians never really broke free. Although they might yet do so. Just like the Jewish people, other people who were enslaved want to return to the mental comfort of slavery – in which they do not decide, but in which they are also not responsible for poor decisions. One could argue that the violent patterns of South American democracy shows that some countries are still struggling for freedom in the aftermath of Simon Bolivar’s revolution from European powers 200 years ago. The granddaddy of revolutions – France and Russia in 1917 were revolts that led almost immediately to a new form of dictatorship.

So what makes a revolution successful? What enables people to actually be free?

It isn’t hard to draw a line. If the people already have a civic culture, that culture can step in and enable a free society to be successful. The trade unions in Poland served this purpose. But if that civic culture – that unspoken law and expectation and sense of responsibility – is lacking, the society disintegrates. It demands a new master. It lacks the tools to function without one.

The great question, of course, is how do you free a society that lacks this cultural underpinning? Late in his life, Bolivar decided that dictatorship was a necessary step on the road to freedom. He needed to teach these civic values through dictatorship. He may not have been wrong. We’ve seen Taiwan emerge as a great free society – from military dictatorship. We’ve seen South Korea do the same. Of course, both of these societies had strong civic underpinning prior to their dictatorships. So it wasn’t unnatural for them to emerge as they did.

So, the question remains: how do we create freedom from slavery?

This is not just an academic question. So much of the world is unfree but their salvation does not simply involve overthrowing governments.

The Torah, in my reading, seems consumed by this issue. G-d Himself seems to struggle with it – suggesting at more than one point that the people just be erased and replaced with something better.

Nonetheless, the process is somewhat successful. It starts with the splitting of the sea. But it continues immediately afterwards.

As pointed out by Rav Bick from Yeshivat Har Etzion, whose online lecture I heard, after the crossing the people are successively denied food and water. They are trained as slaves are trained – in order to follow Torah. That lecture said that they needed to learn three things in a particular order. First a chok (which the rav defined as a command you can’t understand), then Shabbat and then Torah.

This was the path to becoming the Jewish people. It was also the path towards a religious Jewish life for an individual.

I’m going to take his initial idea – that these denials are a way of training slaves – and I’m going to take it in a slightly different direction. My focus, after all, is somewhat different.

Immediately after the crossing, the people come to Marah, where the waters are bitter and undrinkable. For three days, they do not drink. They complain to Moshe who complains who Hashem. Hashem shows Moshe a tree, Moshe tosses it into the waters and the waters become sweet. G-d declares a decree and ordinance and says (to paraphrase): “If you listen to Hashem you will be free of the Egyptian diseases.” This predicament is described as a test. Like the tests of Avraham, the people’s thirst is both a challenge and an opportunity for growth.

So, what is going on here?

On one level, the people are denied water, they are showed the mysterious power of G-d, and then they are given sweet water. They are being trained. But the symbolism of the tree suggests a deeper lessonthan simply following that which you do not understand.Trees are consistently identified as gifts of G-d – think of the Garden and Adam’s fruit. This concept of gift is why there is a commandment not to harvest trees for three years after planting. We intentionally disconnect our act of planting from that of harvesting. Fruit are a gift of G-d.

In this story, the water is bitter. Biologically, water is key to life because it can supply nutrients to cells and remove impurities from them. It is a source of renewal. Water is also a stand-in for spirituality. In Bereshit (Genesis) there are four rivers in the Garden. Two are physical rivers, but two are spiritual. There are spiritual waters that can refresh us or even bring us down.

At this point, the Jewish people have a bitter relationship with G-d’s spiritual essence. They are like kids annoyed at having to take instruction. They are still stuck with the Egyptian mental disease. But then they acting as commanded and put one of G-d’s gifts to them into the water. By doing as they’re told, they make His spiritual waters sweet.

The symbolism as I read it is: by using G-d’s gifts (the commandments), we can appreciate G-d’s spiritual presence. And with that recognition, we can begin to take on the purpose and responsibility that establish the basis of a successful and free nation.

In other words, responsibility starts with an understanding that obeying the higher moral authority is the path towards ultimate reward and success.

Shortly afterwards, the people face another challenge. This time, they have no food. They murmur against Moshe and Aaron. Their complaint is very specific: They wish they had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when they sat by the flesh pots and ate bread to satisfaction; it would have been preferable to dying of hunger in the wilderness.

In response, Hashem says he will cause bread to rain from heaven which the people should collect daily. This bread will teach them that G-d brought them out of Egypt. The bread has a variety of interesting qualities. Among them, no matter how much is collected; each person gets just enough to sustain them for a day. This amount is universally referred to as an omer – seemingly irrespective of the size of the person involved. If people gather too much and try to store it, it is eaten by worms. They must collect it every day and never store it. G-d states that if the people will gather the ma’an every day, and twice as much on the sixth day (to store it for the Sabbath), it will demonstrate that the people will walk within the Torah.

As part of this process, the night before the mahn is delivered, the people look towards the wilderness and the glory of G-d appears in a cloud. It is one of the great revelations of Hashem’s presence that form the backbone of the people’s relationship to G-d. With the delivery of the mahn, the people can see the glory of G-d Himself.

On the first level, G-d’s test involves Shabbat itself. But as with the tree and the bitter waters, there is more going on.

Before this cycle of training is concluded, Hashem tells Moshe to store some of the mahn as evidence of the food G-d has granted the people. Moshe tells Aaron to fill a jar with an omer of the mahn and place it before Hashem. Aaron places the omer before the “testimony.” Then the text notes that the people ate the mahn for forty years, until they came to settled land. And then, the text adds on a particularly incongruous verse: “An omer is one tenth of eipha.”

This final verse is unusual for a few reasons. First, the omer was already in use; it doesn’t need a definition.The city of Omera (Gemorrah) was named after the measure of grain and Kedarlaomer, the leader of thefour kings, was named for his control of the omer. The omer is not new.

As for the tenth of an eipha, it is not used interchangeably as a unit of volume. In later verses, the sin offering and the appointment offering of the Kohanim include the command to bring “one tenth eipha” of flour. The word omer is not used, despite it seeming to be equivalent of one tenth eipha.

So why mention the ratio here?

This ratio is key to understanding the story of the mahn. The omer is the amount of food required to support an individual for a day. Kedarlaomer’s name suggests that he cornered the food people needed in order to survive. Omerah (Gemorrah) was probably named for its agricultural productivity. Here, people eat an omer a day. Later, we are commanded not to collect a leftover omer from the field. It is there for others to consume. It gives the poor sustenance. And we bring an omer of our first grains before G-d as an offering. This offering is a recognition of G-d’s gift of sustenance to the people. It has overwhelmingly positive connotations.

The eipha is different. The root for eipha is to bake. In Joseph’s dream, the place of Egypt is occupied by the baker – who has his head lifted from upon him. When the Egyptians make bread, they bake it. Egypt with its bread and bakers represented the fullness of human self-regard. Those who believe bread is their own product fail to recognize the role and gifts of Hashem. Our sin offering is thus representative of a fraction of that same conceit. We bring 1/10th of an eipha as a sin-offering, not an omer. The eipha is far more negative in its connotations.

Going back to the story of the mahn, it began with the people wished for specific things. They wanted to sit by the flesh pots and eat bread to satisfaction – even if they were to die in Egypt.

How does the mahn address this? The people wanted a temporal satisfaction. They wanted short-term fullness, even if it meant Hashem would have killed them in Egypt.

Specifically, they are drawn to fleshpots and bread.

In answer to their request, Hashem provides an omer for every man, every day except the day of rest – the Shabbat. They are worried about their food, they are not sure they will have enough. They lack trust. The mahn teaches them, trains them, to trust.They are commanded to consume it all each day – trusting that G-d will provide more the following day. So long as they are not in settled lands, where they can grow their own grain, the consumption of the mahn without hoarding is a tremendous sign of divine trust. The worms that eat the leftovers all called Toa’at Shani, these words are used for a color used to indicate trust in the Mishkan. But the lessons go deeper. The Shabbat (spelled שבת) is the substitution for the sava (שבע) they wanted in Egypt. They wanted the sava, satisfaction, they had in Egypt. But as G-d’s people, their destination is not by eating their fill and then dying. Their destination, their path, is one of trusting G-d for the six days of creation and then connecting with G-d on the seventh day of rest. The real road for human fulfillment – trust in the A lmighty and investment in the timeless.

When Aaron places a jar of this food before the “testimony” he is providing a contrast to the people’s initial desire for a ‘pot’ of flesh. The root of the word for testimony (Eid) is a word used for the people themselves. The root used here for jar (tzanen) is only used once later: “Those who remain in Canaan will be a tzanen in the side of the people.” The suggestion is as an unpleasant pain. The jar is placed as an unpleasant reminder of their initial desire for a pot of flesh instead of the far deeper satisfaction of trust in G-d’s sustenance and Hashem’s rest.

We are also told they will be sustained by the mahn for forty years, until they reach settled lands, namely the borders of Canaan. Settled comes from the same root as sitting. They wanted to sit by the flesh pots of Egypt, instead they will come to a settled land and sit with the memory of Hashem’s support.

In this light, the omer and the eipha are compared because that is the contrast the mahn brings out.

- The omer fills a man’s needs. The eipha speaks to man’s conceit.

- The omer (with its trust) is the future of the people, while the eipha (with its conceit) is to be their past.

- Shabbat is to be the road to timeless fulfillment, while eating one’s fill and then dying was the path of satisfaction sought in Egypt.

- The omer is but a fraction of the eipha, but it provides the road towards true satisfaction.

It is with the omer of mahn that the people can trust in G-d, behold His glory and understand that He brought them out of Egypt. The eipha is a testament to nothing.

With this test, trust in the divine and the cycle of six days of work and one of rest is being established within the people. They are being inscribed with the basic morality of a nation in the image and service of G-d. But still, they are taught like slaves. They are taught through denial and then provision.

The mahn is not the last of these tests. There is a third and a fourth test. Once again, it is a denial of water.

When the people are thirsty once again, Moshe complains to G-d. He is angry at the people. But G-d is not angry. Instead, He tells Moshe to take the staff he used to strike the Nile and strike a rock in Horev (where the Torah is given), so that water will come out of it. There is no commandment associated with this action. There is no test connected to it. The lesson is more direct. Just as G-d’s staff can pollute the waters of Egypt, it can provide water in the desert. Egypt’s corrupted spiritual waters were ‘murdered’ by Moshe’s staff. But with a strike, that same staff can draw Hashem’s spirituality out of desert rocks themselves. The message is both a promising and a threatening one. The people are like a desert rock. In Yaacov’s blessing to Yosef he calls him a shepherd of the stone of Israel. The word for stone, then, was even. But the rock here is a tzur. It means ‘neck’. There is a concept of being stiff-necked – to go back to that donkey. This rock is us. The people are bereft of spiritual value. But they can change, even if they must be struck for such growth to occur.

Again, there is denial and provision. But this time, the threat of future suffering is also brought to bear. Of future strikes. The slaves are being retrained through dictatorship.

When we get to Parshat Chukat, we will see quite a contrast with how to deal with the people when they are ready to leave the desert.

It is here that the famous battle of Amalek occurs. Amalek bears a grudge against the children of Israel. In the days of Avraham, there was a war between the four kings and five kings. The name of the leader of the four Kings, Kedarlaomer, suggests that he cornered the grain market. S’dom and Omorah, fertile places, were rebelliously defying his market control and so he went to war with them. Along the way, he took the opportunity to lay waste to other potential competition. Among others, he destroyed the fields of Amalek, fields belonging to an innocent third-party who were not at war with him. He also attacked the pre-cursors of both Sihon and Bashan. Avraham did nothing. After Lot was captured, Avraham attacked and defeated the four kings. He helped after Lot was captured, not before. Because of the ease of his victory, it is clear he could have interceded earlier. But he did not.

Avraham was worried that he has committed a great error. But Hashem reassured him he had not.

Nonetheless, Amalek had a different perspective. Not only did they have a different perspective, but over the intervening 400+ years they nursed their resentment. They maintain it despite G-d’s declaration that Avraham acted appropriately. They have a contrary moral code – one that nurses resentment and anger and destruction.

The battle itself is very unusual. Yehoshua (Joshua) takes an army to attack Amalek. But Moshe climbs a hill. With him are Aaron and Chur. From his very prominent position, Moshe holds up the staff of G-d. The staff of G-d is the tool of G-d – as we just discussed when it was used to strike the rock. Moshe’s arms are supported by Aaron and Chur. Aaron is the one who follows unquestioningly. Chur was a leader of the people for a brief time. He also shares a name with the Churim, one of the other innocent nations ravaged by the Kadarlaomer. This suggests that those who might otherwise feel wronged can be brought to support G-d’s morality.

So long as Moshe holds up G-d’s staff – supported by both those who follow unquestioningly and those who learn to follow – Israel prevails. But when he relaxes (from the root necham), Amalek prevails.

So long as we lift up and represent the will of G-d, we can overcome contrasting moral voices. But when we relax this representation, those other moral voices will be ascendant. And those voices will ultimately be dedicated to our destruction because they are incompatible with us.

After the battle, G-d says to Moshe: “Write this for a memorial (zocher) in the book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly blot out the remembrance (zaicher) of Amalek from under heaven.”

Wiping out the memory of Amalek has nothing to do with forgetting them. There’s no paradox here. It was Amalek’s memory – of nursing resentment for 400 years – that brought them into conflict with the Jewish people. Wiping out their memory is about eliminating their ability to maintain their anger across generations.

Amalek adheres to a moral code which is dedicated to the destruction of the representatives of G-d’s morality; a morality that encourages forgiveness of grudges instead of nursing them – a contrast to the thousand year-old battles that define our neighborhood. Hashem’s promise (and ultimately our responsibility) is to eliminate their ability to maintain those values over time. Amalek is accused not only of attacking the people, but having no fear of G-d. They do not submit to G-d’s morality. This combination of rejection and violence against G-d’s people prompts G-d’s promise that He will eliminate Amalek’s memory from under the heavens.

In a way, Amalek represents the final training of slaves. We are made to defend the morality of Hashem against those who would attack it. As part of this, we are promised victory over those who threaten us.

To this point the people have been trained, like slaves. They are taught that there is spiritual sweetness in the commands of G-d, that there is true satisfaction in the cycle of G-d, that G-d can draw spirituality from them despite their limitations and that when they stand for the morality of G-d they will be ascendant.

Cast into modern times, and a more secular perspective, we can perhaps see the beginnings of a road to freedom:

First is understanding that while the constraint of law seem bitter, they are actually a gift and the first step on the road to the sweetness of freedom

Second, there is true satisfaction in a society that works and rests – aiming for something more than just physical pleasure

Third, even unfree peoples can be a source of great spiritual value

And fourth, so long as those people stand for morality, they will be ascendent.

These are only the first few steps on the road to freedom. We have forty years of learning to follow. But they are critical first steps.

As this is the structural section, I have one last question: if all this is needed to bring us to freedom then why were we ever enslaved? Why not go from Avraham to ever increasing freedom and responsibility.

There is a lesson in the slavery. Hashem brings both good and evil. There is a purpose to it all. Until we accept that evil also has a purpose, we are not ready to be true servants of Hashem. The evil is there to teach us, to raise us up. We have to be able to learn. Perhaps not as individuals, who may not survive. But as a people.

We are the rock that is struck, we are the bush that burns.

Despite it all, Hashem is in control.

When we can understand that – when we can hold up our staff in the face of His enemies – then, like Natan Sharansky – we can be free no matter what our physical reality.

Conclusion

If any of the ideas in this episode help you or appeal to you, then share them. You don’t have to share them in my name; go ahead and steal them. They’ll serve their purpose just a well.

Thank you and Shabbat Shalom,

Joseph Cox

What I didn’t mention in the podcast, is that these ideas serve as the underpinnings for the process of freedom in my book A City on the Heights.

Photo by Robin Canfield on Unsplash