Mishpatim: G-d and Aristotle

This week, I’m not going to do the Five Faces of Torah. We’re going to do all of this in one take walking through the parsha from beginning to end. This parsha has a lot of details and sometimes it can be hard to keep track of the overall plot. I’ll do my best though.

That said, I wrote a story for this week that I published in my Torah Shorts books that really hits on the main points nicely. If you’d like me to post a copy, let me know.

Let’s get started.

Parshat Mishpatim is a collection of laws. They may seem somewhat random, but I believe they have an order. They are showing us a path from slavery to the realization of our full potential.

Laws of Misfortune & Civil Crime

This reading starts with slavery, as I just said. Notice that nobody is guilty for putting the person in slavery. It has simply happened due to extreme circumstances, just as it happened to the people in Egypt. Despite this, there are rules. Male slavery – which is focused on labor – has a time limit, it has a time horizon. It is limited. Female slavery – which is assumed to lead to things other than the use of labor – is only for marriage. Despite the extreme reality that would lead to enslavement, we do not allow the suspension of law. Even in this case, law puts a boundary on the deprivations of reality. Destruction is limited.

The process of making a slave permanent shows the cost of such a decision, the decision to become a permant slave. The slave must drive an awl through his ears and into a doorpost. Through our ears, we listen; specifically, we listen to G-d. By driving an awl through his ear, the slave signifies that that connection is fractured. By driving it into the doorpost, the slave is subsumed by the family. He is a part of their identity. But he doesn’t have his own identity. He himself is not dedicated to Hashem, he is dedicated to them. After interviewing Jack France in 2022, I realized it also might mark the end of what we listen to and aspire to. The slave is deciding to never step through the door to freedom.

After the marker of slavery, we switch to the most direct crimes (hitting hard enough to kill) and then move slowly down the severity and intent ladder. The next group of laws continue in this human-enforced vein. They offer hope. They offer legal management of disputes. They preserve opportunity. They make the law the breathing force of social stability. And, like the laws of almost every society, they limit destruction within the community. They have a lot in common with standard legal codes of the region.

Jewish-Specific Laws

As the laws proceed, though, they begin to more specifically relate to the Jewish people. Like an organism growing from seed, the people start off looking like any other Mesopotamian society – but soon they shift into something distinct.

Laws of Marriage

The first indication of something distinct comes with the laws of marriage. Marriage seems like an obvious idea that is universally connected to religion, but that is only a reflection of the influence of these ideas. After all, Yehuda sleeps with a prostitute who is called a Kadeisha – almost a holy woman. Societies, including Midian, used prostitution and orgy (both of which inherently confused the relationship between fathers and children) as a part of their religious practice.

In contrast, the Torah is focused strongly on the idea of an unbroken and clear chain from parents to children forming the basis of an unending relationship with G-d. This process depends on providing for children, but also on protecting the traceability of that parental lineage from Har Sinai to the present day.

In a way, there is a mutual obligation to support one another’s capabilities. Only a woman has the potential to bear a child. Only a woman can provide an environment that provides for a fetus. A man can’t undermine that, he has to support the woman. Likewise, only a male has the reproductive will to inseminate a woman. A woman can’t undermine the expression of that will by clouding who the father of a child is.

We see that in the laws here. If a man sleeps with a betrothed virgin, he becomes obligated to marry her, should her father approve. If the father doesn’t approve, the man must pay. The man exercised his procreative will and the woman – who provides the environment within which the child will be cared for – must in turn be provided for. And, right after this law, we are then commanded to ensure sorceresses don’t live. Unlike the magicians of Egypt, who could imitate the plagues, the sorcerers of Egypt accomplished nothing. They seem to employ slight-of-hand rather than actual magic or science. Interestingly, this law specifically concerns female sorcerers. The reason a seduced virgin is entitled to marriage or money is because whatever child she has will clearly be hers. The man is cast as a seducer, he is the guilty part, not the other way around. A female illusionist can undermine society in even more fundamental ways by clouding the relationship between fathers and children.

These laws of Jewish distinction start with broken relationships because they are a corollary to murder. A society in general is undermined by murder, but a Jewish society in particular is undermined by broken relationships – family relationships.

Bestiality (very specific and human-directed)

The next law involves sexual intercourse with animals. While this may seem like an ordinary prohibition to modern Western eyes, it could also be considered a ‘victimless’ crime. The practice is far from unheard of in many regions of the world. Khomeini’s little Blue Book has the following law: “A man who has had sexual relations with an animal, such as a sheep, may not eat its meat.” This normalizes this practice.

The prohibition on bestiality is the next step. To waste your reproductive opportunity doesn’t undermine the families that define a society, but it does symbolically waste the power to create and build in this world. It distances us from the divine example.

Sacrificing to others: Core of Our Distinct Identity

Finally, we come to sacrificing to other gods. Those who do so are to be not just killed, but annihilated. To sacrifice to another G-d is to dedicate your physical creation to their values – or at least their power. Where many ancient civilizations accepted a broad pantheon of divine figures, our society is not to have elements dedicated to contrary value systems. Modern American civilization would seem not to share this approach. After all, religious toleration is key to the Constitution. But even modern Americans do not tolerate those who undermine the Constitutional order. They can be shunned or even executed. Even the most liberal of western nations have fundamental values which they defend coercively. And I would say the sets of values being defended coercively are expanding. If they were to fail to do so, then they would risk elimination through the undermining of their own identities.

This law, the enforcement of the most basic aspect of the divine nation’s mission, is the last in this set of socially enforced laws. It is also the most distinct. It not only maintains a society – it maintains the core values of this society.

All of the socially enforced laws speak to ‘bad apples’ within a society. But a society can, as a whole, go bad as well. And so we have two externally enforced laws at the end. They demand that strangers, widows and orphans not be afflicted. With this, we fight against real-world risk. And they demand that the lending with interest or take a man’s only garment as collateral be prohibited. With this, we ignore real-world risk. We take steps towards holiness itself.

The punishment for infractions against these statutes is delivered by G-d because their violations indicate not damaged individuals, but a society that is itself damaged.

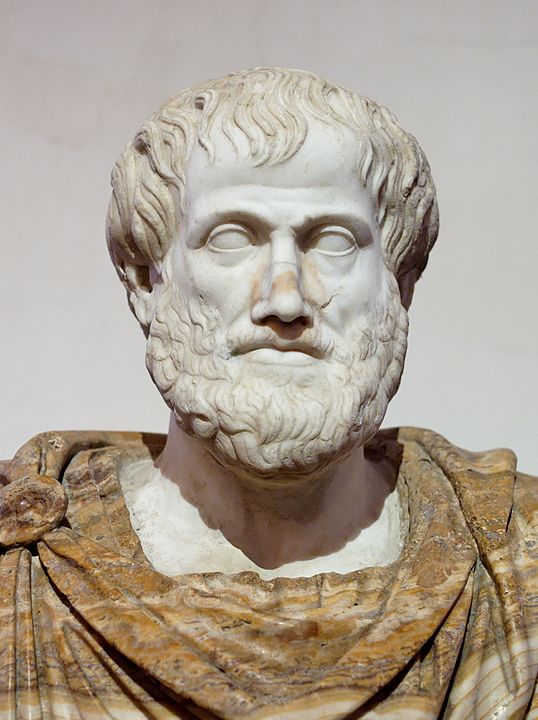

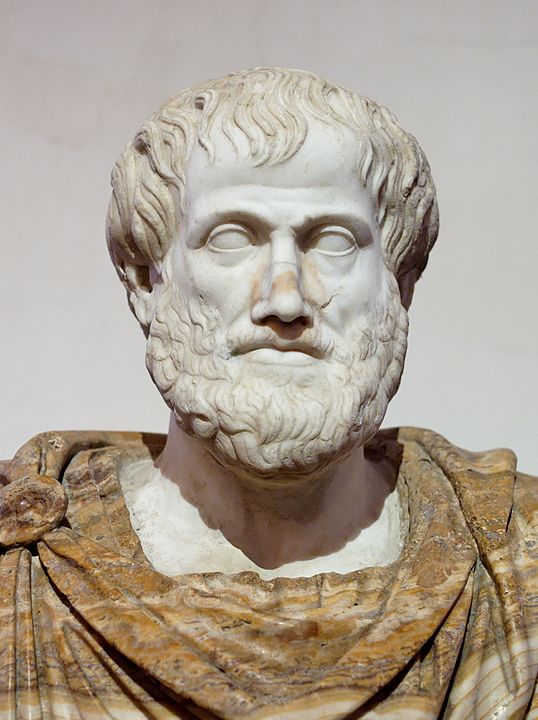

To recap the socially enforced laws, we can see a trend from generalization towards distinction. But we also have a process of habituation. As Aristotle wrote: “Moral virtue… is formed by habit… We become just by the practice of just actions, self-controlled by exercising self-control and courageous by performing acts of courage.”

In this Parsha, the people are becoming divine through a circle of habituation. Habituation to limit the worst of circumstance. Habituation to, step by step, limit the destruction of a society. To make it function as any society would. But then it continues, with habituation to make us ever more G-dly and distinct. As we are habituated, the need for social and direct punishment falls away. We can continue on the path towards divine virtue with the positive experience of that path being sufficient to habituate us to it.

Investment in Law

Judges and Princes

This process of positive habituation continues with respect for the law itself. Fear of the law is driven by punishment, but respect is far greater and more effective. The world is full of legal codes that have little impact on real life. To grow beyond what is enforced, we need to have respect for the law itself. This is why we are commanded not to revile G-dly judges or curse a prince within the people. A prince is not simply a powerful person – this is a prince within the people – not somebody who lords over them. In a way, we’re respecting the legitimate judicial and executive branches of the society. Legislation is handled by Hashem.

We then continue this habituation with some initial steps on the road towards investing and protect our relationship to G-d.

We invest by dedicate the gifts of the first-born and full crops to G-d. And we protect by giving torn meat to dogs, instead of eating it. A torn animal does not die in an act which dedicates to a higher purpose – it dies due to natural risks. Its death is not connected to the spiritual or physical growth of people. The meat is thus tainted with an association with this loss. By giving the meat to dogs, it serves a purpose without undermining our spiritual standing.

Respecting judges is only step one. We take it further when we are commanded to act fairly and honestly in matters of justice; our own personal prejudices and relationships should not blind us from what is appropriate. We also don’t punish the innocent (such as a donkey) just because they are under the control of the guilty. Having invested in law, we can execute it fairly. We can come to respect it and obey it because of that respect.

With these laws we have a society with the tools necessary for a self-regulating, stable and generally accepted legal system.

Laws of Holiness

All of this provides the baseline for an ever-stronger divine relationship. What follows are the laws of that relationship. All lack any explicit punishment – they are simply an opportunity to draw closer to the divine. That closeness is its own reward.

Investment of Divine Blessing: Shabbat & Chagim

Initially, we see the laws of the Sabbatical and the Sabbath. These reflect the investment of production in timeless rest. Both the Sabbath and the Sabbatical are opportunities to imitate the divine cycle. Next, we see that we are not to mention other gods. While sacrificing to other gods was punished by death – delivered by the society itself – here any acknowledgement of those gods is forbidden. By voluntarily excluding other value systems, we draw even closer to G-d. We are then commanded to have three yearly holidays. The first, for Passover, was commanded before. But the next two are connected to the harvest and ingathering of produce. They are commanded here for the first time. In this context, they all speak to a joyful recognition of the blessings of the divine. We are not just investing our funds in the Sabbath, we are investing our souls in the festivals of the Lord. Like the offerings of the first-born, these laws represent an investment in building the divine relationship.

Protecting the Divine Relationship

Leavening & Fats

The final group of laws captures the flip side of this investment – protection of it. First, we do not offer leavened bread. In almost all circumstances, an offering of leavening would represent spiritual theft because leavening adds to bread almost without human effort, unlike the grinding of flour. Offering leavening involves bringing that which does not represent our own labor.

We also are not to let the fats of our offerings remain until morning. Among other things, the inner fats being referenced, the visceral fats, physically protect the organs and provide an emergency source of energy. An animal is able to survive extreme adversity because these inner fats. They are thus are a physiological representation of resistance to loss within the individual animal. Just as our investments in timelessness are holy, the fats are a physiological representation of holiness within the animal. We have no right to disregard these products. To do so would be an act of spiritual waste.

First Fruits & Milk

Next, we are commanded to bring first choice fruits to G-d’s house. This would seem to be an investment in the divine relationship, not a protection of it. But the first fruits are not like other produce. We are generally forbidden from offering fruit; fruit trees and their products are a gift from G-d and do not represent our own effort and investment. The gift of these fruit is not an investment in the divine relationship, instead it is an acknowledgement of G-d’s beneficence to us. It thus protects the divine relationship by preserving G-d’s position in it. Finally, we are commanded not to cook a kid in its mother’s milk. Where the fats discussed before preserve the animal from moment to moment, the milk preserves the species from generation to generation. The milk is a hopeful and promising connection to the future. By cooking a kid in its mother’s milk, we destroy the milk’s spiritual value. We commit a fundamental act of spiritual nullification. We protect the spiritual, we do not nullify it.

What we see is a pattern of habituation, a pattern of growth, whereby we can learn how to protect and grow the spiritual within our society and within ourselves.

G-d’s Investment in the People

Of course, as with any good relationship, our relationship with G-d isn’t built by one party alone. G-d also invests in the people. And so, he promises His angel will accompany them to the land and that He will defend them. He promises them that they will be able to live in a more lossless world, a world in which bread and water are filled with potential (or blessing), a world without sickness and a world in which people live full lives. Most critically, He promises a world without miscarriages or barren women. We invest our future in G-d, and, in turn, he provides us with that future. He promises us a land waiting for us, with those who worship other ideals driven away. We are to build and maintain that relationship. By doing so, it becomes possible for us to serve as a beacon of the divine in this world.

We see here that the people are rising towards the transformation towards the yovel that they missed at Har Sinai -and that law is bringing them there.

An Offering to G-d (and the people)?

With the people now established and with the core of their national identity and national life defined, they can finally do what Yitro did before the giving of the Torah: they can bring an offering to G-d. Prior to this point, no national offerings had been brought to G-d. The Pascal lamb was offered by small groups of families not by tribes or by the nation.

In preparation for the offering, Moshe builds twelve pillars; one for each tribe. Then the youth offer twelve oxen. As before, oxen represent a generic nation. The offerings are described as both transfer (oleh) offerings and complete conversion (zevach shelamim) offerings. In essence, the tribes are giving the totality of themselves – not just their future – to G-d. Those who bring complete conversion offerings place themselves within the offering. As the youth represent an undefined and hopeful future, they also represent the nation. By placing themselves within the oxen, they represent a young nation dedicating the entirety of itself to G-d.

In a unique procedure, the blood of these offerings is sprinkled on both the altar and the people. This sprinkling of blood carries with it ominous undertones. While the shared dedication of the animal’s spiritual will binds the children of Israel and G-d together, it also raises the people up to dizzying heights.

They are in some ways being compared to G-d as equals. The pillars which represent the people strengthen this image. This enhanced self-image will manifest itself in very negative ways.

But before things take a turn for the worst, the people reiterate their commitment to the covenant. Moshe reads the Book of the Covenant and the people ratify it once again. This time they utter the famous phrase “We will do and we will harken.” It is almost like they are quoting Aristotle. By carrying out these commands, the people will learn to harken. They will be habituated to becoming a G-dly society.

G-d’s Feast

With this recommitment, G-d reciprocates both people’s dedication and their offerings. He brings Moshe, Aaron, two of Aaron’s sons and the seventy elders of Israel to a feast of His own. While there, they see the G-d of Israel. They are so comfortable that they eat and drink and are not endangered. With the addition of the laws, there is no terror even when in the face of G-d. They overcome the terror that overcame them at Har Sinai. In this scene, the G-d of Israel is described as having his legs on a floor of sapphire as pure as the heavens. This speaks to the power of the relationship. The heavens represent a world without loss; nothing is dead in the sky (aside from some possible simian additions since satellite programs started). Even dead birds fall to the ground. Because of this distance from loss, the heavens are called tahor. G-d’s feet are on a sapphire brick. The work for brick is boneh (to ‘build’ or ‘form’). The word for sapphire comes from the root saper which also means ‘book’. The Jewish people had just ‘signed’ a Book of Covenant with Hashem so the ‘G-d of Israel,’ the G-d of this relationship, stands on the forming of the book of the covenant. And this forming is as distant from loss as the heavens. It is full of potential and it has not suffered any failures.

It is in this situation that the elders see Hashem himself, not just the Elohei Yisrael – the G-d of Israel. But they don’t Ro’eh, literally see. Instead, they chazo – they have a vision of G-d. They can have some appreciation for the totality of Hashem’s power.

It is on this foundation, a foundation of law, of trust, of potential, of dedication and of understanding, that G-d invites the people to build the mishkan (Tabernacle) so that He may dwell among them.

Conclusion

As we seek to rebuild our modern relationship with G-d, we must take careful stock of the nature of these laws. This section’s code is a twist on the legal codes of its time and place. Those codes are reemphasized with a focus on preserving individual potential, preserving the timeless chain of our society and reinforcing our dedication to divine values. Perhaps, in modern times, we should do the same – twisting our modern state’s legal systems towards an emphasis on these same values. Instead of individual rights, we should focus on individual potential and we should start by limiting the damage caused to those with the greatest misfortune. Instead of atomic pleasure in the here and now, we should emphasize the far more fulfilling commitment to the past and future.

Our Story

All of this begs a question: What does this legal story-telling add to our ability to lead an impactful life as individuals and as a nation? Why not just catalog all the laws by subject matter? Shouldn’t all laws about murder should be in one area with all the laws about property damage in another. Why have a story?

As we read the national story, we should apply it to ourselves. As the nation steps through the uneven process of growth that those who left Egypt went through, we should walk the same path.

As we personally walk the path of the Exodus we can experience these transitions. We are brought out from Egypt – a four-year-old child at a Seder understands this. In time, we take on the beginnings of responsibility and we fail to trust G-d in the face of death. We learn to regulate ourselves. We draw close once again. Step by step, we develop. We habituate to a relationship with Hashem. The path is far from straight, but with it we can become greater than the most obedient of angels.

So, what can the future hold? Perhaps it can bring the design and construction of the mishkan – the place where G-d can dwell within us. And perhaps it can bring us the Yovel – a world without pain and loss and suffering.

We will see more in the readings to come.

Once again, if you enjoyed any of the ideas in this episode, feel free to share them.

Thank you for listening and Shabbat Shalom.

Pingback:Jack France & Mishpatim | Joseph Cox