Shemot: Yaira’s Bat Mitzvah

This episode contains my speech in honor of my daughter’s Bat Mitzvah. You can read it below or listen here.

This episode is another Torah-focused podcast. Like last week, I’ll structure it around 5 faces of Torah: inspirational, political, trivial, structural, and finally my answers to standard questions.

Inspirational

This episode is not quite the standard episode for a simple reason. My daughter Yaira’s Bat Mitzvah was two weeks ago. I didn’t speak about it then. It is a bit embarrassing, but the simple reason is that – in the absence of synagogue services – we hadn’t had our eye on her Hebrew birthday. We’d been too busy planning the party she wants – and will eventually get – to properly mark her actual Bat Mitzvah. She remembered it, about 20 minutes prior to candle lighting. She lit candles for the first time and that was how we marked it.

The fact remains, synagogue or not, that my favorite part of a Bat Mitzvah (especially for my own children) is not the Kiddush or the party. My favorite part is my last chance to pass on fatherly advice in public and maybe have my child listen.

In the absence of a speech in synagogue, I’m going to make one here. Hopefully, she’ll listen.

This speech will be about both the reading two weeks ago and this one.

As you’ll see, the delay may well have been fortuitous.

If you really want to get in the mood, wake up earlier than you want to and sit in a slightly uncomfortable chair for an hour and a half. Then groan quietly to yourself as I, the father of the Bat Mitzvah, gets up to speak.

Sometimes the parallels between the Torah and our present day are extremely simple to draw. This is one of those occasions. The famine in the Joseph story is presented as an international catastrophe. It affects Canaan as aggressively as it affects Egypt. Despite its scale, Joseph’s capable administration guides Egypt through the crises. Today, we are faced with an international catastrophe. As we compare notes on our various cultures and societies, no government resembles Joseph’s more than that of China.

Confidently, smoothly, Joseph brings the people through the famine and out to the other side.

His administration must have been the envy of the ancient world.

We admire his success even today, but this Torah reading reminds us that there is a dark side to it.

A successful central planner always runs the risk of thinking too much of themselves. Of replacing dynamism with planning. Of eliminating choice in favor of a scientifically controlled outcome. Of creating harmony at the cost of humanity. Of forgetting that a crisis is just that – and the solutions for a crisis (which require single-mindedness) are not the solutions for the reality to follow (in which many goods compete).

The result can be disastrous.

I think Yosef meant well. Back in Parshat Miketz, my daughter’s Bat Mitzvah parsha, Yosef saw a problem, he saw a solution and he had a plan – a good plan.

Unfortunately, that plan ultimately undermines both Egypt and the children of Yaacov. The Egyptians beg Yosef to buy them so long as they can stay alive. They become the property of Pharaoh and are resettled at the whim of Yosef. They lose their lands and possessions and become legally enslaved sharecroppers. The Canaanites, as recorded in Chapter 47, give up all their money to the Egyptian regime. And the children of Yaacov are paid an allowance by the child. Yosef takes care of them, but along the way, they lose their will to run and their initiative.

Clearly, they still shepherded their animals. They were still free. But that allowance, even if it was just enough to feed their children, kept them tied to Egypt.

The entire time, Pharaoh – the central administration of Egypt – became more and more powerful.

What follows is almost inevitable. Everybody but Pharaoh is enslaved – Egyptian and Jew alike. Pharaoh himself forgets that he is not inherently ordained to have the power Yosef has granted him. The Egyptian people, barely functioning, fear that the Children of Israel will leave. They aren’t afraid of rebellion, they are afraid the Jews will leave. The Egyptians have lost their own economic vitality. The Children of Israel – the only free people in Egypt aside from the priests who are not economically productive – are providing it. Everybody is in thrall to the great central power.

While the children of Israel are initially not slaves, they are also not paragons of freedom and self-determination. The Torah describes them as multiplying, using the same word as is used for bugs. They are paid an allowance by the child and so children are created. They multiply like bugs. Even in this, they lack initiative. They do not fill the land, instead the text says “the land filled itself with them.”

At the same time that they are multiplying and seeming to grow ever stronger, they are passive and weak and easily enslaved.

What is described is an economic and social catastrophe for the Egyptian and the Jewish people alike – even before the slavery and the plagues. It all goes hand in hand with the growth of Pharaoh’s power.

In today’s world, we have the Chinese Communist Party in the place of Pharaoh. The same people responsible for the suppression of information that let the virus flourish in Wuhan – and delayed the world’s response to it – are riding high on their own belated but overwhelming reaction. Few Chinese have died. Their all-powerful government has used the catastrophe to justify and further cement their position.

They represent the Yosef of this story. They represent the effectiveness of a central power in an all-consuming crisis – and the weakness of such a power when the crisis is not their sole focus, as in Wuhan. Just like Yosef, they are protecting their own people while enslaving them. At the same time, they have ensnared the rest of the world just like the children of Yaacov were ensnared. Using their advantages in scale and cost, the Chinese Communist Party has induced the West to give up almost every bit of their intellectual property – all in the name of cheaper manufacturing and the false promise of equal access to a major market.

Like the Children of Yaacov, the world has bound itself into a trap – giving up their own edge and initiative in return for a small economic benefit. A benefit they are unwilling to sacrifice – despite the increasingly obvious costs that benefit demands. Like a gradually cooked frog, we are only realizing our predicament when it is too late.

Just as with the Children of Yaacov, the West has increasingly given up its freedom and independence in return for a little money.

As we emerge from this crisis, this process will almost certainly accelerate. The economic weakness of profligate Western governments that managed this virus poorly will be leveraged by increasingly powerful Chinese state. Loans to Africa, that will be leveraged into power over raw materials will be mirrored by loans to the West that will guarantee there is no source of resistance to the great Chinese Communist Party project.

Xi Jinping’s China Dream is very real.

With the coronavirus, a catastrophe is going being turned into a nightmare.

And, just as with Yosef, the Chinese people will themselves be among those suffering the most.

So why would any of this matter for my daughter’s Bat Mitzvah?

The answer comes in this week’s reading.

Pharaoh’s rule is not without end. What seems unbreakable does, in fact, break. But the cracks that form in this seemingly unbreakable reality do not come from strong men. Even after the project of freedom begins, the men who lead the Jewish people demand that it stop.

No, the cracks in this reality are formed by women. Women willing to break the rules and shatter the system that surrounds them.

First, we have Shifra and Puah, who defy the order to kill all newborn boys.

Second, we have Miriam who encourages her parents to have another child despite the horrors of their world.

Third, we have Moshe’s mother who refuses to kill her child because she sees that he is good.

Fifth, we have Tziporrah – who rescues Moshe from his own reluctance.

And rewinding back to fourth, we have Pharaoh’s daughter. The deaths of the Jewish boys should make sense to her. The power of her family is so deeply tied into her father’s project that it should be obvious that her own interests demand that the Jewish people be suppressed. Her own interests should demand that the Jewish boys be killed.

And yet she goes to the river – knowing there are likely to be children there. She notices Moshe’s floating cradle and she has it retrieved – knowing it is likely to contain a child. She saves it – knowing it is a Hebrew boy. When Miriam comes and offers a nursemaid, she accepts – knowing that in a world bereft of living baby boys – the nursemaid is most likely to be the boy’s own mother. She even lets the child be raised – until it is weaned – in its own mother’s house.

Pharaoh’s daughter is an agent of chaos, and a catalyst for freedom.

Despite everything that should make sense to her – she does something different.

Shifra, Puah, Miriam and Yocheved resist. But they are protecting their own. Pharaoh’s daughter resists because it seems like she cannot help but resist.

She wasn’t suffering, but her resistance is what opens the door to redemption.

Yaira, you are an agent of chaos. We try to run a reasonable house, a rational house. We try to never lie to you. We always try lay out our reasoning clearly. We try to lay out our case clearly, so that you (and all of our children) will work with us simply because it makes sense. But ever since you were a little girl, whenever something made too much sense, you simply refused to comply. You went off on complete tangents precisely when the logic for doing so was weakest.

I don’t think you had any particular reasoning behind those decisions. Like Pharoah’s daughter, you couldn’t help but challenge the constraints of order, even at the cost of your own self-interest.

Yaira, you are incredibly hard-working and diligent – as your cards project showed. Anybody listening can email me to discover what I’m talking about. Yaira made over 50 three dimensional cards and sold them for 30 shekel apiece, giving all the money to Alyn Hospital. But the aspects that represent you more clearly are your creativity and your humor – both of which are based on that central plank of your existence. You are an agent of chaos. Your humor is unexpected and creativity must always be so.

Yaira, not only are you an agent of chaos, you live in a land of chaos. Israel is not the West, drowning in debt, childless and sclerotic. Israel is not an authoritarian state, threatening the freedom of the world. Israel, by the very virtue of her relative weakness, is willing to work with many other nations. The United States might be our great ally for now – but it is not hard to foresee a future in which are connections to others states grow even more important. Within our own borders, things happen haphazardly. Israelis don’t plan very well. Nonetheless, they still happen. Israel punches far above her own weight.

Israel is like you – creative, diligent, hard-working – and quite averse to a planned reality.

I fear that as the world is transformed in the wake of the coronavirus, the freedom of humanity will be dependent on those willing to be agents of chaos. Of those willing to do what is right even when it makes no sense. Especially when it makes no sense in the short term.

It will depend on those willing to create cracks in an increasingly perfect – and nightmarish – global society.

It will be dependent on the daughter’s of Pharaoh.

It will be dependent on the likes of you.

Women as a whole do not resist the actions of Pharaoh. Only a few do. None resist the program at its origin, in the time of Yosef himself. Asnat, Yosef’s wife, did not undermine her husband’s plan to parlay food into domination. Imagine the pain and death that could have been avoided if she had.

Imagine if, unlike this dvar Torah, the cracks in the system had been timely.

But they weren’t.

No, Yaira, what you have is rare.

Few, blessed with brains and beauty and the blessings we have given you, have the guts to challenge their own reality.

But you do.

I can honestly say that it hasn’t been easy, raising an agent of chaos. Even as I’ve seen you gain more and more control over that chaos. Of course, the most important things are often the hardest to accomplish. And I already know your mother and I are proud of whatever part we will have played in your eventual accomplishments.

Yaira, may G-d grant you a future of unending blessings.

May you play your part in defying order and reason.

May you use your powers for good.

And may all of us be blessed by your example.

We love you.

Political

After that last bit, you probably couldn’t imagine how I could get more political. Of course, I won’t. The political section is more about ideology.

There’s a remarkable scene early in Moshe’s story. Moshe comes to Midian and sits down by a well. Shortly afterwards, the seven daughters of Yitro – the priest of Midian – show up to water their flocks. They are soon chased away by other shepherds. Moshe stands up and rescues them and then waters their flock. They go home and their father asks them how they managed to get home so quickly. They explain that an Egyptian man rescued them and helped them. He then asks why they didn’t invite him home. We fast forward a bit and Moshe eventually marries one of the daughters.

This story is the third in a series of matrimonial well stories. The stories show vast changes across times and societies. In a way, the well stories can be used as a barometer of the health of a society.

In the first story, Eliezer comes to Abraham’s family. Laban is still a young man, and hasn’t yet poisoned his society. The Torah tells us that women draw water for the flocks. Rivka (Rebecca) is one of them. Rivka proceeds to water Eliezer’s animals and then invites Eliezer to her home, and actually brings him with her.

In the next episode, the society has lost trust. There is a rock covering the well, and all the shepherds must be there to lift it. Now, instead of women watering the flock, there are men. Rachel is the only woman there. Yaacov rolls the stone off single-handedly and then waters Rachel’s flock. Rachel then runs home to tell her father and her father invites Yaacov home.

Finally, we have Moshe’s case. In Midian, the nation which draws the ire of Hashem in the book of Bamidbar (Numbers), the male shepherds actively chase the women away – a regular occurrence. The shepherds don’t just fail to trust each other, they are allied against the weak. In addition, all seven sisters com to the well together – they can’t go alone. Moshe chases the shepherds away and waters the flock. The sisters head home, but don’t think to invite Moshe.

We have three progressions here. Women go from exclusively drawing water and watering flocks to being chased away when they try to draw water. Women go from being able to go to the well alone to needing to travel in groups, for safety. And women go from being willing and able to invite a foreign man home to not even thinking of the possibility.

The picture that is being painted is of a world in which women are being squeezed out of a core part of economic life – and fear for their safety in public.

Later, Tziporah shows herself to be no shrinking violet. Of course, that is later. Perhaps Moshe, raised by a strong and independent woman, brings out this characteristic in his own wife.

All in all, I think the Torah is showing us healthy and unhealthy societies. What is showing us is that a healthy society is one in which women are not locked away and do not live in fear.

Interestingly, almost all the great men in Torah are shepherds – from Avraham to David. But, at least in this early period, many of the great women also start as shepherds – including Rivka, Rachel and Tziporah. The wives of Yitzchak, Yaacov and Moshe were not the women who stayed at home.

Trivial

#1: When Pharaoh asks the midwives why they can’t kill the Jewish boys, the midwives explain that the Jewish women are like “Chayot” or wild animals. Rashi explains that this meant they were experts and didn’t need a midwife’s help. There’s an interesting mathematical bit that can explain this. Later, when counting the first-born, the Torah says there are 22,273 of them. 22,273 in a nation of 600,000 men. This would suggest roughly 30 male children for each woman. The standard response to this is to suggest that there were 30 male children per woman. Of course, that doesn’t work, because if there were then the whole nation would have numbered roughly 22,273 men the prior generation. This is not the numerous people described in the Torah.

There is another, simpler answer. The women gave birth to girls first. With this, the number of first-born males might only include those born after the Exodus. In addition, when it came time to deliver boys, the women would already have been experts.

#2: Moshe is consistently identified as an Egyptian. Like Abraham and Yosef, he crossed cultures. This ability to move across cultures is critical – not only to connecting to other societies but to changing your own.

#3: Moshe is given three miracles to display his bonafides. These miracles, through their symbolism, show the story of the Exodus in advance.

Nachoshet – copper – is the practical metal of the Bible. The Nachash, or snake – same root – is the tool of G-d. When Moshe’s staff turns into a Nachash – a snake – the symbolism is that the staff of Moshe is the tool of Hashem. Moshe’s role is to represent Hashem – to act as Hashem – during the Exodus.

If the people don’t go for that, there is the second miracle. Tzarat – the Biblical skin condition – would have no meaning for the people. Not yet. As an entirely unknown disease it would also show that Moshe’s actions (signified by his hand) are impacted by a new kind of power. Later, it will be come to signify a divine response to excessive human conceit. This miracle shows the role of G-d in the Exodus. It combines “I will be what I will be” with the blunting of human pride.

The third sign is to take the water of the river and pour it on the land where it will become blood. Blood is represented as the animating soul of the body – it connects our living cells by delivering oxygen. The blood of the river is the lifeblood of Egypt. Moshe spills it onto the ground like the blood of a murdered man. It shows the role of Egypt in the upcoming story.

These three miracles show us what will happen with Moshe, G-d and Egypt.

#4: Moshe turns aside to the bush precisely because it burns and is not consumed. It is not only unnatural – it is unnatural in a very specific way. It shows the possibility of creation without destruction. It is a beautiful and intriguing image. In our world, creation always requires destruction – only G-d can create without destroying. Ultimately, so much of Biblical symbolism is tied to this idea – of creation without destruction. It starts with the Menorah. With branches and knobs and blossoms it burns but is never consumed. The Menorah represents the burning bush and both captures the essence of what our people are meant to represent in this world and what Hashem actually does represent.

#5: We know from the text that the Menorah represents an almond. Wild almonds produce cyanide. Approaching a burning one was incredibly risky. Moshe’s drive to understand the divine overwhelmed his practical fears.

#6: Avraham, Yitchak, Yaacov, Yosef and Yehudah all grow as people. They all learned some new characteristic. Moshe’s very first act is an act of protection. As I read it, unlike his predecessors, he never changes. He never augments that core. Moshe defies G-d Himself in his protection of the people.

Structural

Even after meeting Hashem, Moshe does not rush to Egypt. When he does finally go to Egypt, G-d leaves him with one final message: Moshe is to tell Pharaoh that Israel is the first-born son of G-d. And because that son has not been freed, Pharaoh’s first born will be killed.

It seems like an odd allusion. But it ties the slavery and the beginning of the Exodus beautifully into the book Bereshit (Genesis).

Prior to the flood, we see the decline of society. The sons of Lamech capture the essence of this decline. He has three sons with names related to acquisition. These sons acquire wealth, but there is a suggestion that they do not create it. There is Yaval, whose name means acquisition, who acquires and separates from mankind to do it. There is Yuval whose name means passive acquisition who acquires passively through the entertainment industry – there is a suggestion of the sex trade as well. And then there is Tuval Cain whose name suggests aggressive acquisition. He makes his money through the arms business.

Soon enough, the world has declined. Men of fame and glory take whatever women they please. The seeking of fame is a zero-sum game – to earn it, others must lose it. These men, these great famous glorious men, are called the bnei elohim. The word elohim is used to describe G-d, but the word actually comes from the same origin as All-h. It means power. Judges are thus called elohim, later in the Torah. The sons of the elohim are the sons of the powerful. They didn’t even acquire their power for themselves, it was handed to them by their fathers.

Well, look at this reading. Who has had more power handed to him than any person in history? It would be Pharaoh, enabled by Yosef. He is one of the bnei elohim. But G-d is telling him that the Jewish people are the true bnei El-him.

The connection is actually far stronger than that. In Lech Lecha, G-d famously promises Avraham that his descendants will be exiled. But he doesn’t say where they will be exiled to. An earlier Pharaoh makes that decision for Him.

14 And it came to pass, that, when Abram was come into Egypt, the Egyptians beheld the woman that she was very fair. 15 And the princes of Pharaoh saw her, and praised her to Pharaoh; and the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house… 17 And the LORD plagued Pharaoh and his house with great plagues because of Sarai Abram’s wife.

That Pharaoh acted exactly like one of the sons of elohim. He saw a woman he wanted and took her. Yes, he paid Abraham – but there was no consent. Not only that, but G-d brought plagues on Pharaoh’s house. And the text never said He lifted them.

What we have then is the story of the slavery actually closing out lessons lingering from the book of Bereshit (Genesis).

Those full of pride will be brought low. The sons of elohim, who take whatever women they want, will be taught their place. The world will learn as well.

There is one more critical thread. In Lech Lecha, Avraham is promised many descendants and he believes. But then he is promised the land and he asks G-d, how can I know? There are reasons for his doubt and tremendous symbolism in G-d responds. I can share that when we circle back to that reading. But the core message is that Avraham has doubt. Because of that doubt, Avraham’s descendants will be enslaved and then G-d will rescue them. In all of human history, up until the Haitian revolt, a people has never freed itself from slavery. The message to the Jewish people is the same as the message to Pharaoh. Hashem is all-powerful – we should trust in Hashem just as the bnei elohim should fear Him.

Moshe’s core characteristic is that he stands up for the weak. We see it from the very first action he takes. If we, the Jewish people, are to stand against the sons of elohim – the sons of the powerful who oppress the powerless – we must recognize that our own children are the children of another El-him. The El-him. Hashem: the unification of all the higher powers of our world.

Questions

#1: What’s up with Tziporah declaring that Moshe is the bridegroom of blood? Let’s revisit the story. G-d visits a reluctant Moshe along the way to Egypt. He intends to kill him. Why? Because Moshe’s son isn’t circumcised. Circumcision signals that our reproductive will – the most fundamental will of any animal – is not simply biological. Instead, we are dedicating our reproductive capability to continuing the relationship with G-d.

By not circumcising his son, Moshe hasn’t committed his own children to the divine relationship. His own son won’t be a son of El-him. Moshe, who has always had some of Egypt in him, seems to be hedging his bets. As Moshe is unwilling to commit his own progeny to the divine mission, he is unworthy of leadership. And without leadership, he has no purpose and no point in living.

It is Moshe’s wife, Tziporah, who doesn’t hedge. Moshe is dying. With her connection to G-d fading, she circumcises her son, connecting him to the Children of Israel. She casts the foreskins at Moshe’s feet and calls him a “bridegroom of bloods.” Bloods, in plural, signifies blood outside the body. It signifies death. She has married one who is dead. But because of this action, G-d releases Moshe. Tziporah then declares that Moshe is the “bridegroom of blood, with the circumcision.” Moshe is her husband of bloods – but not the bloods spilt through death, but the bloods spilt through circumcision and connection to Hashem.

He is her connection to the divine covenant. No death is required, only a dedication of future generations to G-d – as a members of the Jewish people.

#2: How can the Egyptians suffer as they do – they aren’t really guilty after all? The answer comes back to Yosef. He robbed them of their humanity when he robbed them of their will. By being lowered, they can be used to make an example.

#3: Why is Moshe so reluctant to do G-d’s bidding? I can explain this by looking at a more contemporary example. Imagine if G-d came to you as a German Jew and said: “I’m going to make an example of Germany. I’m going to raise up the strongest single man in history. He’s going to enslave my people and commit genocide against them. I will then free my people and lead them back to the land I have promised them. But along the way millions will die – not only 6 million Jews, but 6 million Germans.”

Would you be excited? Or would you resist? Moshe resists.

I believe Hashem seeks out those who will resist. Those who can’t accept the divine perspective. After all, G-d calls and Aaron comes running. But Aaron is not chosen as the leader of the people.

Conclusion

I think I’m going to start concluding these podcasts in a standard way. First, I’m sharing these podcasts because I want to help people realize their full potential. Whether that potential is creative, holy or a combination of the two, it is a pity when potential goes to waste. That is my goal. I think it is closely tied to the core concept of Judaism – we want to create without destroying, just like the burning bush. We don’t want to waste anything.

I want to help people do that with their own lives.

So, if you’ve found these ideas help you in either of these pursuits, of being creative or holy, then share them. You don’t have to share them in my name, go ahead and steal them, change them, make them your own and carry them forward.

Finally, I’ve made put one of my books up, free of charge at http://JosephCox.com/agent.The Hidden Agent is a thriller about the nature of blessing and curse. The book is free because it has no place in today’s commercial literary market. I won’t cloud you with fake humility – it’s a good book and I think you’ll enjoy it. I wrote it for my kids – if you enjoyed the speech for my daughter you might enjoy it too.

Shabbat Shalom!

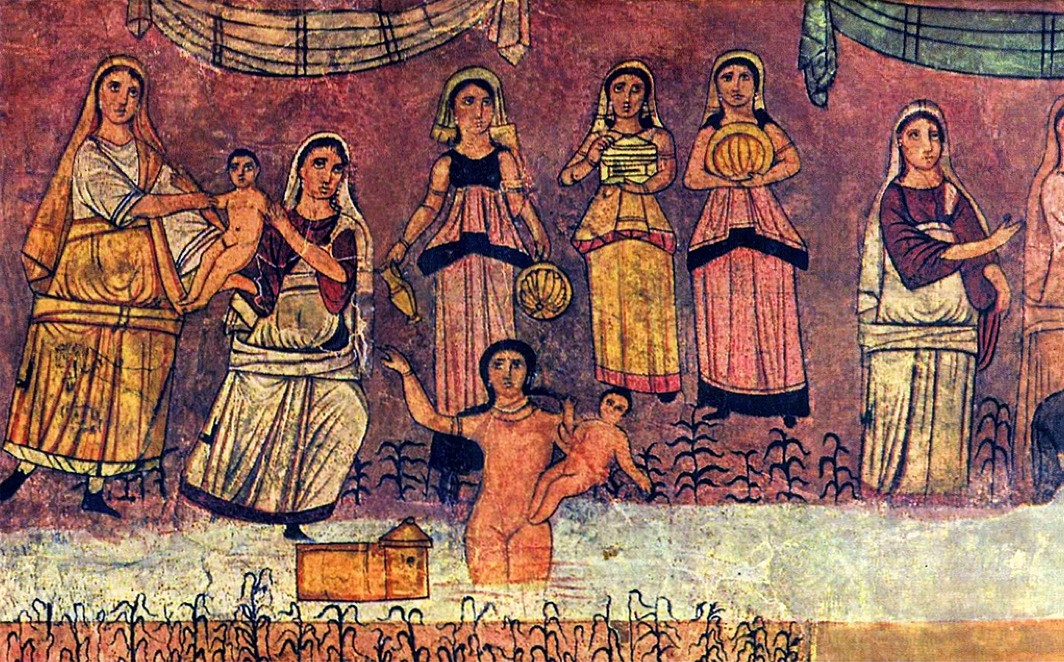

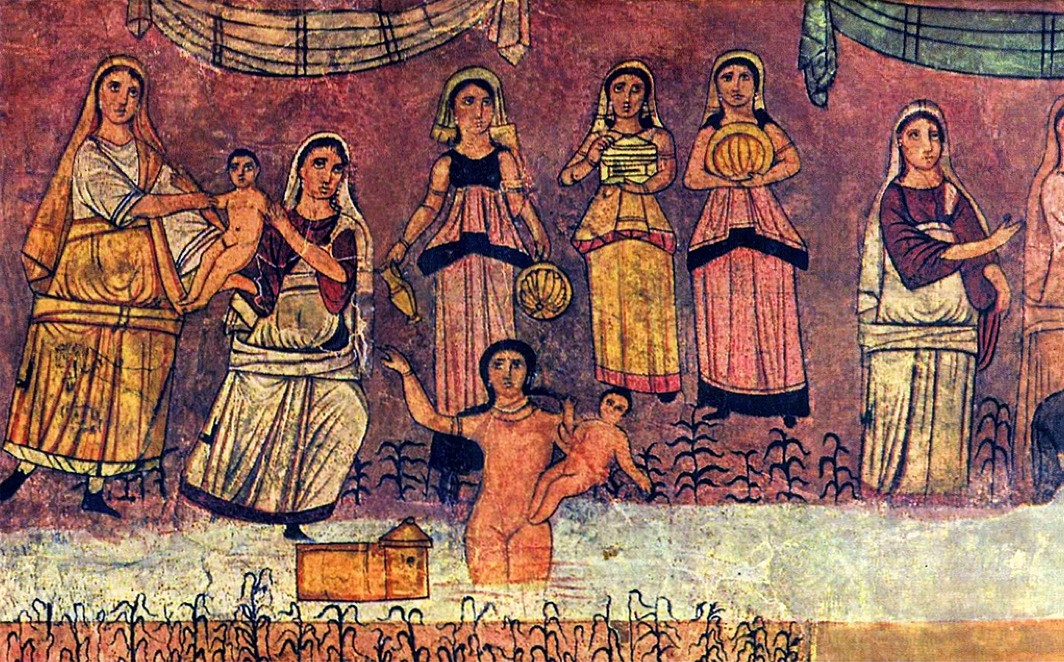

Image: Fresco from Dura Europos synagogue