Va’eira: The G-d of Light and Darkness

Text Below, audio here…

I am really embarrassed. Somebody ordered 5 copies of Grobar and the Mind Control Potion online. Why am I embarrassed? Because I republished Grobar and assumed my stored text matched the previously published version from 2001. It didn’t. It is full of typos.

I haven’t fixed it because I’ve been pretty busy and because Grobar hasn’t sold a copy in years.

So, if you’re reading, I apologize to whoever ordered 5 copies.

Whoever ordered these books, I’ll make you a deal. Send me a copy with the typos you find and I’ll order you 5 NEW copies that are repaired ?If you make the changes in a Word file I send you, I’ll order you 10 NEW copies. I’ll take advantage of you because now I’ve only sold 5 copies in the last few years and I still lack time to fix them up.

My newer books, from City on the Heights on, are in far better shape. I’ve written 8 of them, so you ought to be okay.

This episode is another Torah-focused podcast. Like last week, I’ll structure it around 5 faces of Torah: inspirational, political, trivial, structural, and finally my answers to standard questions.

Inspirational

When you’re looking for positive inspiration, this Torah reading is a hard place to find it.

After all, it is almost all doom and gloom and destruction.

To go along with the helping of darkness, this reading raises some of the most fundamental questions in all of Torah.

How can Hashem rob Pharaoh of his own free will in order to make an example of him?

How can Hashem cause so many people to suffer so much just to make a point about His own power?

Is G-d really just showing his might – justifying Himself through the adage that might makes right?

Is that all that counts?

Is Hashem just because He is totally powerful?

On a first reading, that seems to be so.

Even Pharaoh believes it.

After the plague of hail, he says: ‘I have sinned this time; the LORD is righteous, and I and my people are wicked.

But his understanding yields him no respite.

This argument, this bowing before force, grants him no freedom from the plagues.

We know, from the very beginning, that Hashem has a program. Everything is meant as a demonstration. And Pharaoh, the human foil, will be forced through all the steps no matter what he wants.

So, what are we to learn from this?

Is it that G-d is right because G-d is powerful and that He doesn’t care what we want or how we react? Are we simply unwilling parts in the play?

If this were the case, though, why bother with the demonstration?

Who would Hashem be demonstrating to?

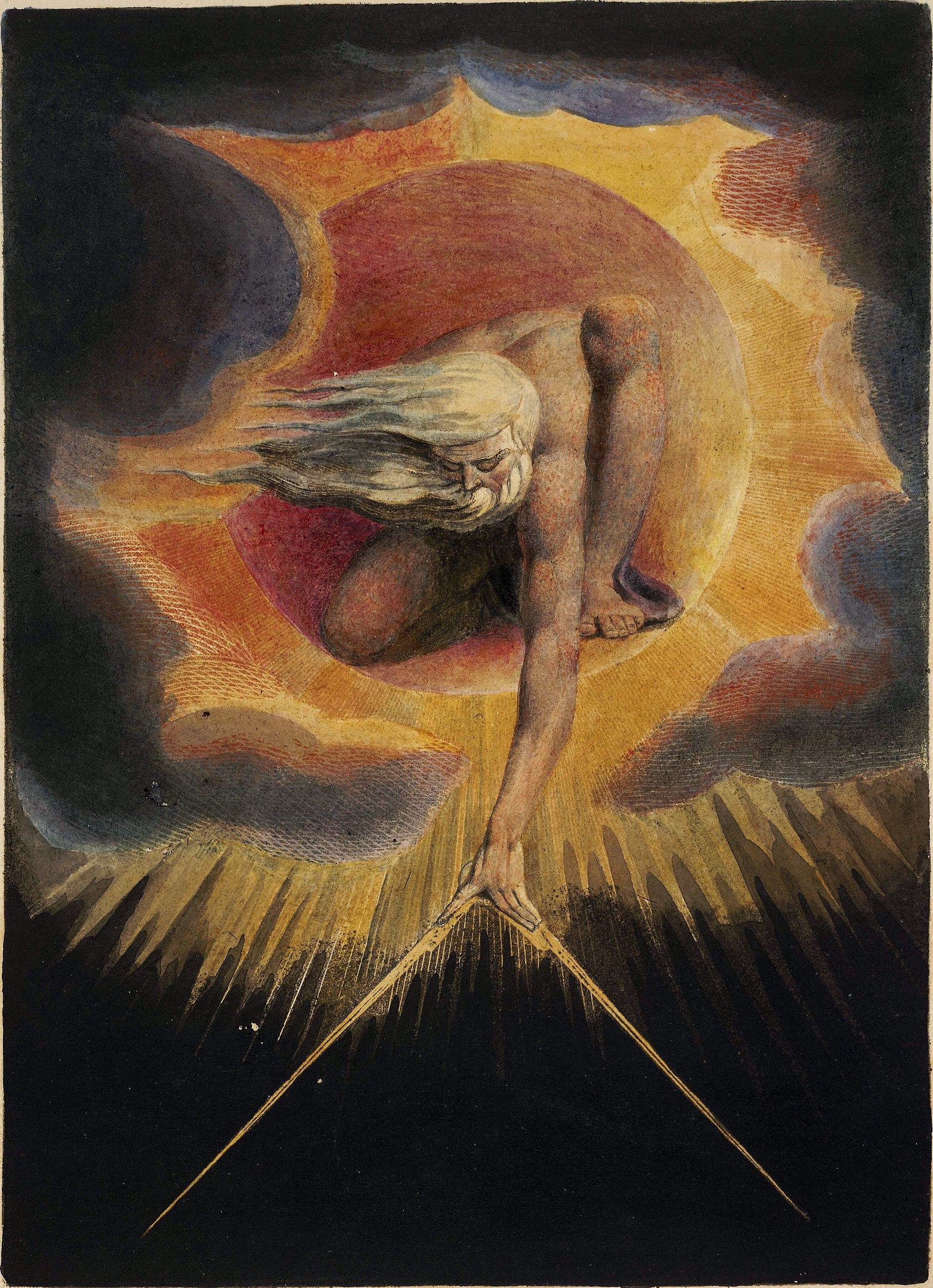

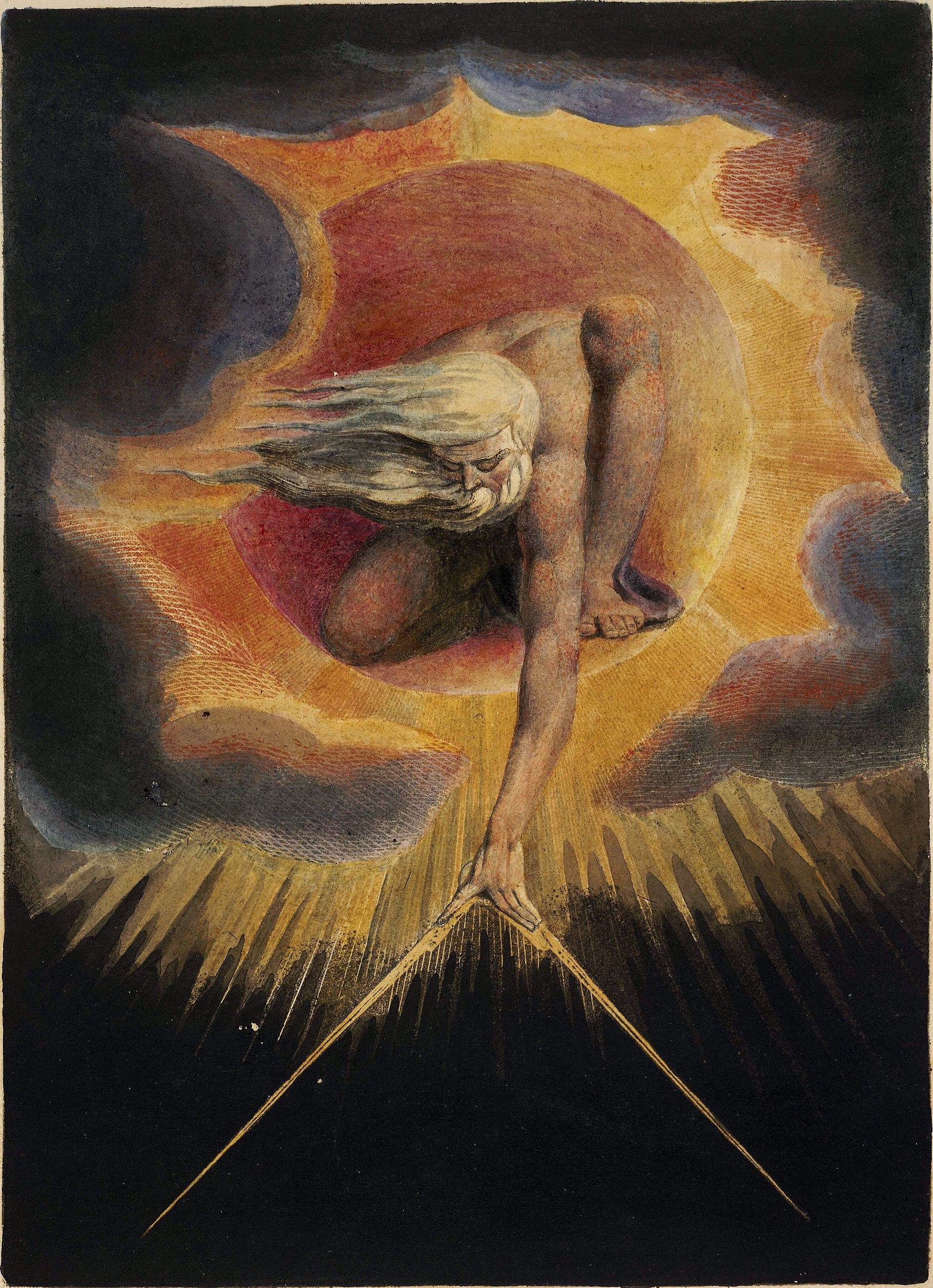

In the face of this G-d of total power and total disregard, we have theG-d of the burning bush.

The G-d of fire without consumption, of creation without destruction.

The G-d who brought the world into being and breathed His spirit into us.

Where, amidst the plagues, is that G-d and how can you square these two visions of G-d – one with the other?

This challenge lays at the origins of the slavery and the Exodus.

Back in Parshat Lech Lecha, before the dark Brit between the parts, Hashem says to Avram “I am the G-d who brought you out of Ur Kasdim.”

‘Ur Kasdim’ literally means Destroyers of Light.

There’s an obvious issue: Avram was already in Charan when Hashem told him to “Lech Lecha” or “get yourself from your land.”

It was Terach, his father, who left Ur Kasdim. The only hint we get as to why is this verse:

And Haran died in the presence of his father Terah in the land of his nativity, in Ur Kasdim.

My brother died in the presence of my father. And my parents fled the place where it happened.

The implication, as I see it, is that Terach was driven out of Ur Kasdim by the death of his son.

When Hashem says: “I am the G-d who brought you out of Ur Kasdim, to give you this land to inherit it” Hashem is saying, as I read it, “I killed your brother. All so that you could inherit this land.”

In response, Avram says: “How can I know that I will inherit it?”

Avram doubts. Perhaps even Avram can’t square the G-d of blessing and promise with the G-d who took his brother. If Hashem has all the power, then who else took his brother?

G-d’s reaction is the dark covenant between the parts. The covenant in which Hashem promises that Avram’s descendants will learn.

G-d, the same G-d of blessing and creation and Shabbat rest, will be the one who enslaves them and then rescues them from their slavery. And not just from Egypt. That brit refers to furnaces and an unparalleled darkness. I think it is referring to the Holocaust.

Even after the Exodus from Egypt, these same questions are raised.

After the story of the Exodus, we can have no doubt as to G-d’s power.

But just as the suffering enhances our Fear of G-d, it seems that it must force our Love to recede.

Moshe faces the same challenge Avram did.

He is attracted to the Sneh, the burning bush. He is attracted to creation without destruction. He is a good man. And so he resists G-d’s program. He resists the role he is given. He prays, fervently, for the plagues to be lifted. He prays, fervently, for Pharaoh to back down. Moshe fights Hashem – perhaps more than he fights Pharaoh. And yet, just as with Avram, G-d chooses Moshe to be a leader of the people.

If our story was just about might makes right, Aaron – who obeys – would be the one who was lifted up to lead.

But he isn’t.

Something else must be going on.

I believe we can find our answer all the way back in the story of the Garden of Eden.

Adam and Chava (Eve) weren’t expelled for eating the fruit.

They were expelled because, when G-d accused them, they both passed the buck.

Adam blamed Chava. And Chava blamed the snake.

Then they were expelled.

The G-d of creation made decisions, acted, judged and created. G-d’s very being was defined by responsibility and willfullness – by the ability to make a decision, speak it and have it be so.

Mankind was meant for this, we were supposed to be in the image of G-d, but we never achieved it.

G-d wanted people who would take responsibility.

If we could not learn in the Garden, then the harshness of the world would have to teach us.

Later, with Cain, Hashem tells says to him – to paraphrase for clarity: “If you do well, your countenance will be lifted up and if you do not, then sin is waiting at the door. But because it desires you, you can rule it.”

Hashem wants Cain to take responsibility.

The temptations of sin are there to lift up his own self-power his own wilfillness. G-d wants Cain to cultivate this aspect of the divine within himself. It might seem counterintuitive, but his ability to rise up is enabled by his own weaknesses.

Coming back to our story, we have two men of responsibility.

We have Moshe. Moshe who resists because he is a protector – of the weak and of women and even of sheep. Moshe is a good and holy man before he is the leader of the people.

And we have Pharaoh. Pharaoh is also responsible. He is in control. But his sense of self-determination is wrapped up in the service of his own pride. Pharaoh is there to be made an example of.

But what of the Egyptians and the Bnei Yisrael?

What of those who suffer the most? Who lose their crops, who go hungry?

These people, these masses of people, act without responsibility.

In the face of the program of enslavement, neither one resists.

In the face of freedom, the Bnei Yisrael shrink away.

And in the face of the first nine plagues, the Egyptians act only in the smallest of ways. They bring in their flocks to protect them from the hail and that’s it.

So when do the plagues end?

They don’t end when Pharaoh is overcome. Pharaoh is overcome by the sixth plague.

The plagues end when the passivity of the peoples ends.

The Jewish people take the little action of offering the Pascal offering – of setting themselves apart from Egypt.

And the Egyptian people actually push the Jewish people out.

Not Pharaoh, not the officers, the people.

In the end, the Torah says that Hashem gave the Jewish people grace in the eyes of Egypt.

Perhaps the Egyptians recognized that the plagues and the suffering had actually lifted them up.

In that moment they realized that they could actually be responsible for their own lives. The Egyptians were also enslaved, the Torah makes that clear in the story of Yosef. But on the night that they pushed the Jewish people out, the Egyptian people learned to free themselves.

In the Hidden Agent, my thriller on Blessing and Curse, I said that G-d’s art lays in men’s (or women’s) souls. But He uses pain and pleasure and suffering and challenge and blessing to craft those souls.

That is what I see here. We see two entire cultures lifted through suffering.

We can’t understand it from within the story. Moshe can’t understand it as it is happening. We can barely understand it from a distance.

But that perspective is still there.

G-d can both be the G-d of creation and rest, of goodness and holiness – and the G-d of plague and death and pain.

The suffering, as hard as it can be for us to conceive it, can be in service of the our souls.

We have a spark of divinity, but when we allow ourselves to be guided like cattle then we lose that spark. Hashem is saying it is better not to have life than it is not to live.

The plagues are a demonstration. But they aren’t a demonstration of G-d’s power in the service of G-d’s pride. They are a demonstration of G-d’s commitment to us.

We might imagine we are powerless in the face of great men like Pharaoh, but we always have the power to take responsibility.

We may not understand His ways, but Hashem redeems us from the destroyers of light nonetheless.

Political

This, of course, has been a very interesting week politically.

I’m not going to directly speak to any side in the ongoing troubles. I have my opinions, but in our present reality, people stop listening if you don’t say exactly what they already believe in.

I’ll share something and I’ll let you make of it what you will.

This week’s reading is a lesson on the limits of human pride – and it is a lesson on the importance of taking responsibility, as individuals.

Pharaoh was a prideful man and Hashem liberated us from Him.

It is our obligation to do the same today.

We must take responsibility.

Now before you jump to conclusions on where I stand on present-day events, let me add one more wrinkle.

Pharaoh is never given a name. He isn’t called Ramses or Amenhotep. He is just called Pharaoh.

That is because Pharaoh isn’t protecting his own pride. His is protecting the pride of his institution.

The position of Pharaoh, although it certainly morphed and changed, was almost ten times as old as the US Constitution. It was almost as old as Christianity is today.

On the other hand, Moshe represented no institution. He had no constituency. He was Hashem’s messenger, but didn’t even support G-d’s program.

Nonetheless, he is a Leader. Why? Because he wants to lift his people up.

To me the lesson is clear: in the face of prideful men or even prideful institutions we must lift ourselves up.

We exist to maximize and realize our own G-dly potential, and the potential of others. We exist to maximize our potential for creation and for engaging with the timeless.

We are not meant to be slaves to the pride of others; and we are not meant to be slaves of fear. We are not meant to be slaves of institutions.

We are free, given our freedom by an Almighty G-d.

No matter what the challenges, it is up to us to use that freedom well.

Ultimately, that is what defines our souls.

Trivial

#1: There is a genealogy in this reading. But it is extremely limited. It seems that, in the face of slavery, only three of the tribes offer any resistance. Only three keep their own leaders. First, are the children of Reuven, the proud oldest son. They maintain their leaders for a generation. Second, are the children of Shimon – the willful destroyers of Shechem – who also survive for a generation. And third, are the children of Levi – who also helped destroyed Shechem. Unlike the others, they survive to the time of Moshe and Aaron, and beyond. In total, they provide five generations of leadership under slavery.

This genealogy is telling us about the state of the people. Aside from Moshe, Aaron and Aaron’s sons they have no men of note. They have no leaders. They are weak.

There is another message though. Moshe and Aaron are leaders, even though they have no followers. The route to our national survival has come through their families because without their families the Bnei Yisrael might have had no national identity at all.

#2: Moshe complains that he has עֲרַל שְׂפָתַיִם – which we translate as uncircumcised lips. Later, the word Aral is used to describe a restriction or a blockage. Our hearts have an Aral and it prevents us from serving Hashem. In Egypt, as I understand it, prophecy involved speaking the inspirations of a god without blockage. The words of the god would come freely from within you.

I think Moshe’s Aral is not his speech impediment – it is a his unwillingness to speak the words of Hashem. Moshe has not agreed with G-d’s program. And so Aaron becomes Moshe’s prophet. Even though Moshe can not speak without reservation, Aaron can.

This is both Aaron’s great strength, and his great weakness.

#3: After the plague of Arov, Pharaoh tells Moshe and Aaron they can sacrifice to Hashem in the land. Moshe and Aaron refuse, saying they will sacrifice the Toavat of the Egyptians to Hashem. If they do this, won’t the Egyptians stone them? In other words if they sacrifice in Egypt, the Egyptians will kill them. The word Toavat is generally translated as ‘idol’ – they’ll sacrifice the idols of Egypt. But it actually means ‘abomination.’ Telling Pharaoh they’ll sacrifice what Moshe and Aaron think are abominations wouldn’t make much sense though.

The word Toavat is a culturally relativistic word. Yosef tells his brothers to tell Pharaoh they are shepherds because shepherds are Toavaat to Egypt.

Aaron Pinker, a man who is apparently far more educated than I judging by what I read, suggests that perhaps it is the act of Zevach – of a burnt offerings – that is an abomination. If we move some commas around, the text can be saying exactly this.

Why bring it up? Because it speaks to the same challenging dichotomy. The Egyptians apparently ate all of their offerings. The gods only got that which was beyond human taste or smell. Our G-d instructs us to burn at least a portion of many of our offerings.

In Parshat Vayikra we read of all the offering from the Everyman’s perspective. In that perspective, only one offering, that of grain which is eaten and not burned, is called Holy. The Everyman struggles to see the holy is what appears to be destruction. In the next reading, which has the persepectives of the priests, many offerings are Holy.

The Everyman struggles with this idea, the priests, who are more distant from the act of creation, have an easier time engaging with it.

Squaring these two, seeming destruction and holiness, is the great challenge of worshipping a G-d who creates light and dark.

Structure

I’ve talked a lot about structure on a macro-level already. I want to focus on micro-structure. I want to look at the structure of the plagues.

Before we do, a very quick primer on Egyptian religion from a guy who is not an expert on Egyptian religion. The Egyptians had many gods. But unlike some other ancient polytheistic systems, their gods didn’t really have exclusive control over particular domains. There were numerous Nile gods and numerous Sun gods. They seem to arise in different towns and mix and merge and mashup in weird ways. Their religious system was as much about the relationships between gods as their individual powers. And these relationships were very very fluid. So each god has all sorts of aspects.

The plagues aren’t, with a few exceptions, clearly demonstrations against particular gods. Instead, they are a demonstration of Hashem’s totality. They are a demonstration of an absence of any complex relationships between the many forces the Egyptians saw. There are no relationships in the power of the world, there is only the singularity of Hashem.

Before I step into my understanding of the plagues, there are other ways of looking at these patterns. One view looks at the pattern of choice and warning. Another is about the increasing distinctions made by the plagues – showing the intelligence behind them. And a third is about the historical uniqueness of the plagues. These are all valuable ways of understanding the plagues. If you aren’t familiar with them, I’d suggest you look them up.

My perspective is a little different. It is driven by a desire to understand why we have these plagues in this order. The surrounding superstructure of choice, intelligence and power is also interesting, it just isn’t where I’ll focus.

Within my framework, the basic structure of the plagues is this:

The first seven, in this reading, define G-d’s power in space.

The last three define G-d’s power in time.

As a very quick intro: the plagues start in the river – below. They transition to frogs or crocodiles who come out of the river. Then some lice from the dust of the ground. Then Arov – we’ll get into that – from just above the ground. Then a plague from the Hand of G-d within the animals. Literally the same level as we live in. And then ash cast to heaven falls back to create boils and finally we have hail from heaven.

These seven plagues define G-d as controlling the world from the waters below to the waters above.

The last three are represent death in time.

The locusts are driven by a Ruach Kadiim – which can literally be a ‘preceding spirit’. It destroys the already planted crops. It destroys the life from the past.

The darkness is the experience of death in the present. We can not move. We can not see. It is as if we are dead.

Finally, the killing of the firstborn represents the death of the future.

These three plagues show the power of G-d over time.

Now, on to some specifics. I’m going to be borrowing heavily from Wikipedia on my Egyptian god references.

With the first plague, the Nile turns to blood. These early plagues relate to Egyptian gods.

To borrow from Wikipedia: Khnum was one of the earliest Egyptian deities. He was originally the god of the source of the Nile. Since the annual flooding of the Nile brought with it silt and clay, and its water brought life to its surroundings, Khnum was thought to be the creator of the bodies of human children.

By turning the water to blood, Hashem is not only establishing the baseline of his power, he is killing a central Egyptian G-d. Notably, he is killing the god who crafts children. This is a foreshadowing of what is to come.

The second plague involves either frogs or crocodiles depending on the translation. ‘Tzefardea’ seems like a mash up of two words: Tzipor and Deah. Bird and Knowledge. It is an odd word to describe a creature that lives in the river but can come up on land.

Interestingly, there is a pair of gods this plague could be referring to. Sobek was a god represented as a crocodile. He was invoked as a protector against the dangers presented by the Nile. He also represented Pharaonic power. He is the casualty of this plague.

But he is not alone. There is another relevant G-d: Heqet. Heqet was represented by a frog. The frog was an ancient symbol of fertility. Her priestesses were midwives.

By invading the houses of the Egyptians, the frogs represent retribution for Pharaoh attempting to invade the houses of the Jewish women through midwives.

At least according to one tradition, Heqet and Khnum – gods of the first two plagues, had a child: Horus the Elder. He was a Falcon. His left eye represented the sun and his right the moon (or maybe the other way around). His speckled feathers formed the stars and his wings created wind.

Pharaoh was seen as a manifestation of Horus the Elder

Turning the frog against Pharaoh’s own people and house represented a betrayal of Pharaoh by his own mother. Where Moshe was rescued by his human mother, Pharaoh is betrayed by his divine number.

The third plague is the Kinim. Kinim can also mean ‘foundation’ or ‘base.’ A possible Egyptian god connection is the god Atum, who is seen as the creator god of which all the underlying substance of the world is created. He either sits on the mound that rises from the waters, or is the mound itself. He is the substance of the world and a most fundamental god. All the other gods so far come from him.

He is the first diety.

What we have then is a rising crescendo of divine challenge. As we move from the Nile we face a greater and greater challenge to the Egyptian pantheon.

Perhaps that is why, with this third plague, the Egyptian magicians see the hand of god. They could manipulate Khnum and Heqet and Sobek. Manipulating the foundation material of Atum was another matter altogether. No pun intended.

I think the fourth plague – of Arov – is the last of Egyptian god plagues. Here the reference is to the diming of hope. Arov is translated in different ways, the two most popular being wild animals and flies. Quite a distinction. It literally means ‘twilight’. Erev is evening. It is a time in between, but specifically one of darkening.

The arov will not only fill the houses, they’ll fill the ground they are upon. This suggests not flies, but something that covers the earth, everywhere.

The imagery ties beautifully into one last Egyptian god. Khepri.

Khepri was the god of sunrise. Khepri was represented by the Scarab Beetle. The scarab pushed the sun into the morning sky.

In lieu of a definitive translation, I’ll translate Arov as ‘scarab’.

Where the Scarab normally represented creation and rebirth and hope, the arov flipped this meaning and used the scarab to bring darkness and suffering.

interestingly, the scarab was the most ever-present god for the Egyptian people themselves. The scarab amuluts are the most popular we have found in ancient Egypt. Where Atum is not really a part of daily life, Khepri was.

The fifth plague is also mysterious. It is called dever – or just ‘thing.’ Unlike the lice, this was defined as the hand of G-d in the Torah itself. The Hand of G-d was within the animals.

The true power of Hashem isn’t in the dust, which the Egyptians imagined, but in life itself.

This plague, of course, represents Hashem’s power on our plane.

Then we have the furnace soot thrown to heaven to produce boils when it came back down. The rising of location fits, but the soot part is definitely odd. Why use soot as the starter for this plague?

Everything in a furnace burns, what’s left behind is the soot. The soot has no more energy to give. It is spent. And, yet, Hashem gives it power. When it lands, it creates boils. Almost like it burns again.

We can see another pattern here, Hashem transforms the water, makes various life forms multiply and brings disease. This is the first plague in which he creates something from almost nothing. He reverses the order of things.

Together with the fire hail, this represents a near impossibility.

Finally, this cycle of power over place ends with the hail. The hail is not simply hail, of course. It is a divine hail with near-impossible attributes. There is fire within the ice.

The parsha ends with the hail. Perhaps the division of 7 and 3 – of place vs. time – is the source of this division of readings. In either case, we’ll discuss the sequence of time in more detail next week.

Common Questions

#1: At the beginning of the reading Hashem says the people will know him as Yud-Key-Vav-Key. He then says that the forefathers didn’t know Him by that name. But Yud-Key-Vav-Key is used extensively in Hashem’s interactions with the forefathers. The name Yud-Key-Vav-Key is actually a mashup of the words for Past, Present and Future. Hashem is all that was, is and will be. The forefathers may have known G-d by that name, but they didn’t know Him by that name. They didn’t understand what it meant.

#2: Why does Moshe lie about only going for 3 days? First, there is no obligation to tell the truth to a slaver who doesn’t keep his word.

Traditionally, this sort of lie was a way for everybody involved to maintain their pride.

“They only told me they were going for three days! How was I supposed to know?”

This sort of lie is a face-saver. He wasn’t willing to lose even a bit of his own pride.

#3: How can I say that the Egyptians are enabled as a people when they lose so much at the sea?

When they come to the sea, they use their power in the service of enslavement. They act willingly, willfully. They are no longer slaves. But they do so in the service of robbing freedom from others. This is why they are crushed.

#4: Why did Hashem harden Pharaoh’s heart? I used to think it was just the presence of Hashem that did this – that Pharaoh’s heart was hardened because he knew he was going up against Hashem. But the words used are far too active. Hashem intercedes.

Let’s imagine if he hadn’t.

If Pharaoh had broken earlier, then the totally of Hashem’s power would not have been manifest. Egypt and the Bnei Yisrael would not have taken on any of their own responsibility. All that would have been established is that G-d is greater than Pharaoh.

And if Pharaoh had refused to break? Then even in defeat and death in the Sea, he would have died with his honor intact. He would have resisted. He would have lost. But he would have never stopped resisting.

This is why Hashem had to harden his heart. Pharaoh has to survive, but he also can’t be allowed to lay claim to pride in the face of defeat.

Conclusion

I want to leave with a quick note about the coronavirus. Given the more virulent strains which have struck populations that had earlier appeared to have acquired some kind of immunity the case for shutdowns is stronger. More critically, given the possibility of a limited timeline for the virus, I am now in support of closures.

This is no longer an open-ended problem with a shorter-term resolution only possible through immunity. Those who die now, don’t need to die (at least to a significant degree). We can limit the spread dramatically, for a short while, and we should.

In addition, I want to refer people to TrialSiteNews. It is a website trying to give exposure to medical trials, from all around the world. Their data on Ivermectin is persuasive and there have been many international studies supporting its use.

Just because we have a vaccine doesn’t mean we should close our eyes to the possibility of cheap treatment.

Finally, I’m sharing these podcasts because I want to help people realize their full potential. Whether that potential is creative, holy or a combination of the two, it is a pity when lives go to waste. That is my goal.

So if you’ve found these ideas help you in either of these pursuits, share them. You don’t have to share them in my name, go ahead and steal them. Make them your own and carry them forward.

I referenced The Hidden Agent earlier. It is free of charge on my website, JosephCox.com. It is thriller about the nature of blessing and curse. The book is free because it has no place in today’s literary market. I won’t cloud you with fake humility – it’s a good book and I think you’ll enjoy it.

Shabbat Shalom!